At the heart of ALNAP’s spotlight on learning is the question of why some humanitarian learning contributes to powerful systemic change while other, equally important lessons remain unimplemented. Why does some learning lead to big improvements, as we have seen in the case of cash-based programming, while progress in other areas – localisation being an example –seems stuck?

In our search for an answer we decided to look at systems approaches, which are frequently used when considering organisational learning. One particular model, the Geels Framework, is often pressed into service when considering systems change, and so seemed particularly relevant.

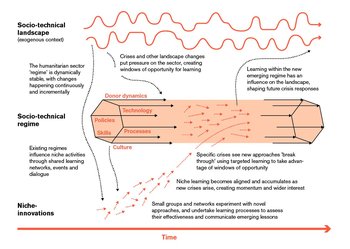

The Geels Framework (below) describes three inter-related levels within a system.

- Niches - spaces where new learning takes place are niches.

- Regimes - the regimes level represents the institutional architecture (in the humanitarian system this includes donors, the UN, Red Cross/Crescent Movement and INGOs)

- Landscapes - the macro factors (social, political, economic) that shape the contextual environment are called landscapes.

I found the model to be useful for the following reasons:

- It is strongly visual, making it easier to think about how forces interact at different levels within a complex system.

- It expands timeframes by focusing on what happens both in crises and between crises.

- It captures stakeholder behaviour and the institutional politics of change, which is often invisible (or partially hidden) in traditional evaluations.

- And it explains why change is episodic rather than linear, happening in fits and starts.

We applied four humanitarian issues to the framework: cash-based programming, localisation, the use of mobile technology and participation. Here is a summary of what we found, beginning with cash.

The story of cash

The humanitarian system resisted the use of cash for at least two decades partly because at the regime level there was an entrenched belief that people in need could not be trusted with money. This belief perfectly reinforced incentives at the landscape level, where food surpluses in the USA and the European Economic Community (now EU) were driving and sustaining the big food aid agencies that were so prominent at the time.

However, small scale experimentation with cash at the niche level was bubbling away, and eventually a report came out that summarised several positive experiences. It showed that cash distribution was both viable and feasible, and that people could be trusted to spend cash wisely.

The findings filtered up to the regime level where cash became a legitimate issue for discussion. This stimulated further research and the evidence base began to grow, which in turn fed discussions among decision makers in operational agencies. Shrinking food mountains in the 1990s meant that alternatives to food aid were being considered at the regime level, and food distribution agencies were looking for innovative ideas.

Then, in 2005, there was a landscape level event. The Indian Ocean Tsunami and the widespread availability of mobile phones created the conditions that allowed for intense experimentation with cash transfers. The cash concept had broken through from the niche to the regime level, the landscape conditions were favourable, and the evidence base was relatively strong. Cash began to ease its way into the mainstream.

'The Indian Ocean Tsunami and the widespread availability of mobile phones created the conditions that allowed for intense experimentation with cash transfers. The cash concept had broken through from the niche to the regime level, the landscape conditions were favourable, and the evidence base was relatively strong'

Later, major earthquakes in Pakistan and Haiti provided further experience and cash networks were established to promote learning and better programming. Geels Framework analysis helps to explain why cash broke through.

Localisation, participation and mobile technologies

The story of localisation has differences and similarities. Localisation also faced problems around a lack of trust at the regime level initially. Although attitudes changed, the localisation opportunities presented by the COVID-19 pandemic – a landscape level event – did not produce lasting change. A number of factors have contributed to this stasis, including continued resistance at the regime level linked to perverse incentives and a lack of breakthrough learning demonstrating viability and feasibility.

'The issue of participation to some extent mirrors that of localisation. Although some niche learning (e.g. the missed opportunity series) has resulted in successful participatory and community-based approaches, especially in technical sectors, there has been no discernible breakthrough at significant scale.'

The case of mobile technologies is more positive. Niche learning around mapping technologies meant that during the 2005 Kenyan elections – a landscape event - opportunities to experiment were seized. Learning provided by Ushahidi and MPesa (amongst others) helped to establish an evidence base that was later enhanced by networks including the Humanitarian Innovation Fund (HiF). There is now a decent amount of research about the risks and opportunities presented by digital technologies, which has helped demonstrate viability and feasibility to regime decision makers.

You can read full accounts of these case studies in the Learning to change paper.

As well as explaining the past, the model also has the potential to inform future change-making. This toolkit on the systemic learning framework is for use by ALNAP members as well as others. We hope that such systemic approaches to learning become more commonplace, and with them, come more focussed strategies for achieving change.