Next week, as senior humanitarians gather for the ECOSOC Humanitarian Affairs Segment (HAS), ALNAP will release the 2025 Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) report, which will have little good news to offer on the state of humanitarian finance. Our analysis will report an already major decline in 2024 and offer scenarios for the likely scale of this year’s cuts, which are expected to be significant. These sudden and drastic cuts have thrown the sector into an existential crisis, prompting a raft of urgent reform proposals and prioritisation exercises. The time for tough choices is upon us.

Humanitarians are no stranger to prioritisation – appeals have always been underfunded, resources always dwarfed by the scale of need. Yet in the current humanitarian reckoning there seems to be a real lack of clarity about prioritisation: about how to approach it, about what is - and isn’t - being prioritised, and why. Diverse priorities – de facto and stated –are pulling in different directions. Cuts are being made at breakneck speed and pursued largely behind closed doors. It’s time for a bit of clear thinking and honest talking about prioritisation.

Since late 2023, ALNAP has been talking with people across the humanitarian sector about the prioritisation challenges they face, including in our podcast series A Matter of Priorities. Building on these insights, we offer the following framework as a way to more clearly consider today’s tough choices.

What do we mean by prioritisation?

Simply put, prioritisation is about making the best use of resources to achieve a given goal – in our case, a humanitarian objective.

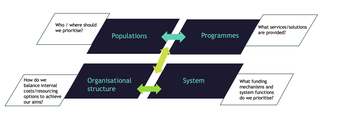

Prioritisation decisions have to be made in four areas – each of which affect the decision-making space for the other:

Populations and programmes get the most airtime in prioritisation discussions – particularly the decisions and boundaries around focussing on ‘life-saving’ and ‘those most in need’. This is about the ‘who’ and ‘what’ of humanitarian action: which populations are targeted where, in which crises, to receive what services and support. It’s also about delineating the kinds of problems humanitarians are willing to address.

The recent urgent reprioritisation of the country Humanitarian Response Plans brought these choices into stark relief: instructed by the ERC’s Reset, country teams drastically cut the numbers of people they sought to reach and the budgets they were requesting – in many cases by more than two-thirds - with little clarity or consistency on how these cuts were arrived at.

Organisational and structural choices are also a matter of priorities. As we are seeing with the present restructures and lay-offs, decisions have to be made on what functions are retained where, at the back-end of HQ and at the front-line of delivery. These organisational choices are being made fast, often dictated less by strategic choice than by where the funding has stopped or which posts are vacant.

At system level, there are prioritisation choices around core functions for enabling a well functioning humanitarian ‘ecosystem’- choices around the right investments in coordination, accountability, and information management. System-level prioritisation is fundamentally challenging because there is no centralised formal decision-making body that determines these priorities, but rather separate, interlinked groups of high-influence agencies.

What are the challenges for prioritisation?

Prioritisation has never been easy – particularly in humanitarian action, which is at the sharpest end of emergency triage. There is very little ethical and practical room for manoeuvre, but there are specific challenges relating to practicalities, to politics and to the purpose of humanitarian action – which are being amplified and shape-shifted right now.

Practical challenges have centred on information asymmetries and gaps for decision-making. this includes information about cost-effectiveness, around funding flows, and crucially around needs data. Right now, the incredibly short timeframes for reprioritisation are compounding these challenges.

Politics - Foreign policy, public mood, and media attention have always played some role in shaping humanitarian priorities. But in our more transactional era, as political drivers become more overt, there is a larger de facto prioritisation at work and thus a shrinking decision-making space for humanitarians.

Core to these practical and political challenges, is a lack of clarity of purpose: the lack of a clear strategic vision of what humanitarian action is for, and the values guiding it. As long as these remain contested and unclear, strategic prioritisation will be hard to achieve.

Five ways to prioritise better

1. Be clear on what we are trying to achieve.

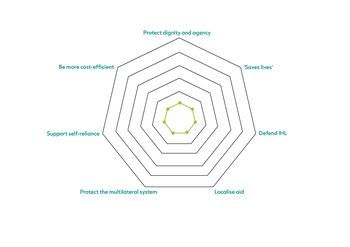

The many statements around resetting and rethinking humanitarian action seem to be trying to address multiple objectives – which can often pulling in different directions. We discerned at least seven different priority aims at play, often within the same statements:

We need clarity about which the real objectives are - so we can reform organisations and systems around them, rather than the opposite: allowing the path-dependence of current structures and processes to determine our aims and values.

It’s ok to have more than one objective, but it won’t be possible to satisfy more than a few simultaneously or with the same structures and approaches. The hard reality is that dialling-up prioritisation of one will mean compromising others, so….

2. … be honest about the trade-offs

Many have been saying this for years: that the humanitarian system is overstretched, trying to be too many things to too many people. But the drastic funding cuts demand harder trade-offs and very new ways of working and structures to mitigate them.

For example ‘putting people at the centre’ and ‘life-saving’ tend to be given equal billing. But we know from decades of efforts that when space is created for crisis affected people to set their own priorities for aid, they often don’t choose what the system determines to be ‘life-saving basics’. Similarly, the impulse to preserve multi-lateral systems in an age of isolationism, has clear tensions with the imperative to localise response. Compromises are possible, but not without honesty about the tensions – and they might be better accepted as compromises if there were more honesty and transparency about what multi-laterals really have to offer crisis settings other than their historical mandates.

3. Recognise that trying to unite the sector around ‘life-saving’ is increasingly problematic.

Despite ‘life saving’ becoming one of the more common phrases to define the scope and priorities of humanitarian action, there is a confusing variety of ways in which this is practically applied in priority-setting When we talk about humanitarians focusing on ‘life saving’ this can mean:

- Whom we are trying to target for assistance (i.e. those in most significant life threatening circumstances)

- The outcomes we are trying to achieve (i.e. reducing excess mortality rates in particular populations)

- The services we are willing to deliver (i.e. food security vs. education)

- The timeframe in which we will operate (i.e. 90 days opposed to 90 months)

Again, all of these are valid, but we need clarity and consistency if we’re not to risk a fundamentally unprincipled approach where humanitarianism is defined differently from crisis to crisis.

4. Be bold in redesigning the system around the goals we say we want it to achieve.

Being clear on what we want, and what we are willing to trade off, needs to be backed with bold and clear-eyed decisions on the actual functions and structures needed to deliver it. Currently operational cuts are speeding ahead of strategy: this needs to be the other way round.

This involves being clear on the specific role and capacity of the multilateral system in particular and where it has most value.

5. No prioritisation in isolation

Closed doors priority setting simply won’t cut it in the face of global system-wide challenges. Faced with structural threats, the tendency is for organisations to turn inward. But isolationism and competition won't cut it if we’re serious about a system re-think – problems of duplication and fragmentation will get worse. Instead of opaque decision-making by pockets of high-influence agencies, we need coordination and inclusion – at least if donors and agencies are serious about maintaining humanitarian action as a shared endeavour for a common good.