Twenty years ago this week international eyes were on the Serb attacks on the supposedly ‘safe area’ of Gorazde in Bosnia and the election of South Africa’s first post-apartheid president. Few outside the region took much notice of the shooting-down of a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi. When the massacres that followed did begin to get media coverage it was always prefaced with “The small central-African state of Rwanda”, a place few had heard of or had much cared about – apart from those who already knew that Rwanda was about to enter a new phase of troubles.

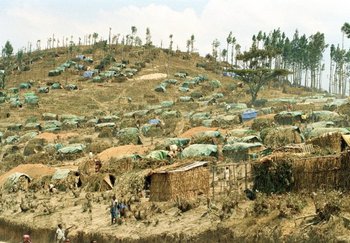

What became known as the Rwandan genocide was beyond even the imaginings of those insiders. As we all know now, the deaths and the mutilations and rapes were organised and systematic. They also led to a civil war that brought in a new government in Rwanda and to the exodus of many hundreds of thousands of Rwandans into Tanzania, Burundi and Zaire, as the DRC then was.

The challenges for the international humanitarian community were beyond our capabilities practically, and threw up many of the challenges that recur at different historical moments in extreme form. How to work the politics alongside the humanitarian response – the saying that humanitarian action cannot substitute for political action is now a commonplace but wasn’t then; how to tell the story to the public without pandering to racist assumptions that this is how ‘they’ behave; how to bring in an emergency response that took account of a development agenda; how to scale up a response on such a scale at an appropriate speed; and all the dilemmas of assisting those who were – generally correctly – seen as perpetrators rather than victims, and mixed in amongst them many armed military and militia. Different agencies responded in different ways, and the arguments about ‘feeding the killers’, for example, go on resonating.

In the end an extraordinary set of responses was launched and some of what was achieved was all but magnificent. But much was also done badly. The best place to find an analysis of all this is still, I think, the Joint Evaluation of the Emergency Assistance to Rwanda.

What came out of it, for me, was a jolt to the humanitarian system that gave impetus to the development of the idea that those in need have rights to assistance and protection – the Sphere Project was already germinating but the failures around Goma especially were evidence of the necessity of standards. Further down the line the long effects on the accountability agenda – ‘forwards accountability’, to those receiving assistance – and the protection agenda are not hard to trace back to what was a traumatic experience for the international system. The Rwandan genocide was their tragedy and only far less so ours to claim as our traumatic experience.

I witnessed some of the genocide at first hand and was part of the responses to it. At the time I thought it was right to call it genocide, because it probably was a genocide but also because that word invoked the rights of those being attacked and was meant to impose an obligation on states to stop it and protect them. As an example of the dilemmas, however, it has also allowed the Rwandan state to invoke the genocide, as Israel invokes the holocaust, to deflect criticism of its actions.

The international responses to the events of Rwanda 20 years ago have in some ways made us more capable, but it is worth not just taking note of the anniversary but making sure that the lessons have not been buried. One general lesson is maybe that there are never right answers or silver bullets. Humanitarian actions and words are fraught with dilemmas and impossible choices, but keeping hold of our history should enable us to make better choices, engage more effectively with the dilemmas and respond better despite the practical strains.