Coherence

Definition

How complementary, coordinated and consistent is humanitarian action across different actors?

Coherence refers to: a) complementarity and coordination of humanitarian action between actors engaged in humanitarian work; and b) alignment with, and consistency between policies and standards, both at organisational and system-wide levels.[1]

Key messages

- Coordination is key to the operational dimension of coherence, to ensure humanitarian actors add value and avoid duplication so that the whole of the humanitarian response is 'greater than the sum of the parts’.

- Complementarity between internationally led and locally led humanitarian action pays attention to power imbalances in the humanitarian system, and how this can constrain or disadvantage local leadership and agency.

- To evaluate the policy dimension of coherence, explore if humanitarian action aligns with international and national policies, if policies and standards are consistent, and how tensions between them have been managed in practice.

9.1: Explanation of definition, and how to use this criterion

Explanation of definition

The coherence criterion encourages a systemic approach to evaluation, rather than a limited programmatic or institution-centric perspective.[2] This means understanding how humanitarian action by one actor relates to the wider system – sectorally, by country and globally.

Evaluate complementarity (see Box 4: Complementarity below) at the operational or programmatic level between humanitarian action by different actors and for different groups affected by crisis. Have different actors added value and avoided duplication? This may include humanitarian advocacy. Coordination is key to achieving this (see Box 5: Coordination below). Explore how internationally led and nationally or locally led humanitarian action complement each other (see Chapter 11).

You can also evaluate coherence at a policy level. How do organisations (individually or collectively) align their humanitarian action with their own policies and standards, or with those of the humanitarian system? Look at consistency between policies and standards and explore synergies or tensions between policy areas. For example, an international humanitarian actor may commit to humanitarian principles, and also have a policy on working across and linking its humanitarian, development and peacebuilding pillars. In some contexts, however, following the principle of neutrality requires maintaining distance from peacebuilding actors and from actors who are party to the conflict. Evaluate how the respective humanitarian actor(s) recognises and manages this tension. Your findings could inform and influence policy revision.

Evaluate how humanitarian actors engage with relevant policies of the government of the country affected by the crisis. Your line of enquiry may vary from one context to another. For example, where the crisis is triggered by a natural hazard such as flooding or drought, or where a government’s refugee policy follows the International Refugee Convention, evaluate the extent to which the humanitarian actor aligns with government policy. In other contexts, where a government is party to the conflict and/or obstructing operational access by humanitarian actors to those affected by the crisis, an appropriate line of enquiry might relate to advocacy with government about its obligations under International Humanitarian Law.

When to select coherence

Coherence is particularly relevant for multi-agency/inter-agency evaluations. Here, explore the extent to which different actors coordinate and complement one another’s work rather than duplicate and/or compete.

Coherence is also important when evaluating international support to locally led humanitarian action. Explore if and how humanitarian action by these different actors is complementary, and how the respective comparative advantage of each is taken into account, including knowledge and capacity (see section 11.2 Locally led humanitarian action).

You can also use the coherence criteria for a single-agency evaluation. If that organisation has multiple mandates, evaluate coherence between its internal policies and system-wide standards. Also analyse if the organisation coordinates with other agencies to add value and avoid duplication.

How coherence relates to other criteria

Coherence relates most closely to inter-connection. Note, the two criteria can be confused, especially if these concepts do not translate easily into different languages. The key distinction is that inter-connection evaluates the nature of the relationship between different types of actors (humanitarian, human rights, development, peacebuilding etc), and coherence focuses on coordination between humanitarian actors. Coherence also evaluates consistency and how tensions are managed at policy level.

Coherence relates to effectiveness and impact too. If an overall humanitarian response is coordinated well within a functioning system, an individual humanitarian actor can take more effective humanitarian action, with the prospect for greater positive impact. To evaluate transformational change, take a systemic approach focusing on relationships and interactions within a system rather than individual components. This is also important for evaluating environmental issues – for example, has the design and coordination of an entire humanitarian response minimised or avoided potential negative environmental effects and promoted resilience? Evaluate the contribution of individual humanitarian actors within that overall analysis.

9.2: Shifting the lens: power and positionality

In evaluating coherence, assess not just alignment with international frameworks, but also how well humanitarian action respects and reinforces local capacities and knowledge. Do the policies that humanitarian actors align with make sense to partners and communities affected by crisis?

Reflect on how your positionality might reinforce dominant narratives or overlook local knowledge. Bias towards formal institutions, for example, can marginalise informal, community-led efforts that are coherent within their context.

Question assumptions that international actors naturally take the lead, especially when their policies override national ones. In some crises, international agencies establish parallel coordination systems, sidelining local authorities and weakening long-term capacity. Or they may influence national systems – such as advocating for the integration of humanitarian cash transfers into social protection frameworks.

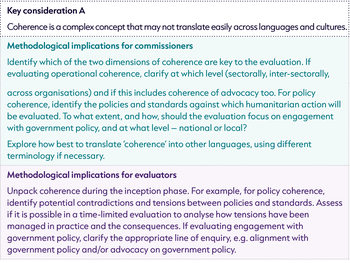

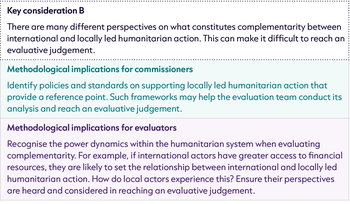

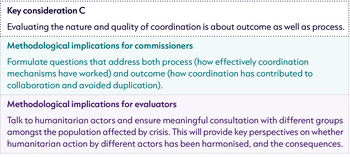

9.3: Methodological implications

9.4: Evaluation examples

9.5: Humanitarian principles and coherence

Footnotes

-

This definition differs significantly from that in ALNAP’s 2006 EHA guide, which is rooted in the response to the Rwanda crisis in 1996 where the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda (JEEAR) concluded that international humanitarian action was a substitute for international political inaction (Borton et al, 1996). In that edition, coherence focuses on consistency between security, developmental, trade and military policies with humanitarian policy. This is outdated and inconsistent with principled humanitarian action. Stakeholders consulted for this 2025 edition requested an updated definition and guidance, unpacking what the criterion means. OECD first used the coherence criterion for development and humanitarian evaluation in 2019.

-

This is also reflected in the OECD definition of coherence.