Getting started – definitions and key terms

2.1: Humanitarian definitions

See annex 1 for a glossary of other useful terms[1]

Humanitarian action

The objectives of humanitarian action are to protect and save lives, to alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity during and in the aftermath of crises, as well as to prevent and strengthen preparedness for the occurrence of such situations.[2]

Evaluation of humanitarian action

EHA is the systematic and objective examination of humanitarian action to determine the worth or significance of an activity, policy or programme, with the intention to draw lessons to improve policy and practice and enhance accountability.[3]

2.2: What is different about EHA?

This guide takes into account a number of challenges specific to EHA in how definitions are adapted from the OECD criteria and their methodological implications.[4]

Conflict, often a cause of humanitarian crises: In EHA, a robust context analysis is needed to understand the political economy of the conflict, which in turn informs an understanding and evaluation of:

- whether the humanitarian response has been sufficiently conflict-sensitive and has succeeded in ‘doing no harm’ in terms of negative consequences for the population affected by the crisis, for example by aggravating conflict dynamics (see CDA, n.d.)

- if and how access has been negotiated with conflict actors

- issues of security and whether a humanitarian actor has adequately addressed duty of care to its staff.

This analysis is also key to understanding and evaluating whether protection needs have been adequately assessed and met.

Accessing and consulting people affected by crisis: Insecurity due to conflict has many consequences. This includes limited or lack of access by evaluators to areas and communities affected by a crisis; people being traumatised, fearful and distrustful of evaluators and possibly of members of their own and other communities; and polarised perspectives. Evaluators need flexible ways to reach those affected, including remote methods and sensitive methods of data collection so all perspectives can be heard. Infrastructural damage from natural hazard may constrain access and cause trauma too.

Lack of documents and reference points: The dynamic, often fast-paced, and sometimes unplanned yet responsive nature of humanitarian action can pose challenges for evaluation. Creativity and adaptability may be needed to find appropriate reference points where there is an absence of planning documents and changing objectives, characterised by an iterative rather than linear approach (see Annex 2 for pointers on adaptive management).

Attribution challenges and power dynamics: Some challenges are common but amplified in EHA. This includes attributing results to a specific action or actor where there may be many humanitarian actors involved, lack of clear responsibility between them, and an unclear relationship between international and national/local actors. Unequal power dynamics can play a part in the latter, which raises issues of who sets the agenda for an evaluation, what is valued and whose perspective counts. Some standards and ethical frameworks for humanitarian action are widely accepted across actors, but they are not universal, as shown below in section 2.5 Relating the criteria to humanitarian principles.

Defining the boundaries of humanitarian action: In many crises, those fulfilling a humanitarian role may have multiple mandates, particularly among national and local actors. And international development actors may also be present. This raises issues for defining what counts as ‘humanitarian action’ to be evaluated, and which population groups are affected directly or indirectly by a humanitarian crisis, as opposed to facing development needs. How could or should humanitarian action relate to engagement for development and peacebuilding, in the spirit of the humanitarian–development–peacebuilding nexus? These issues are particularly acute in protracted humanitarian crises.

2.3: Criteria and priority themes – what are they?

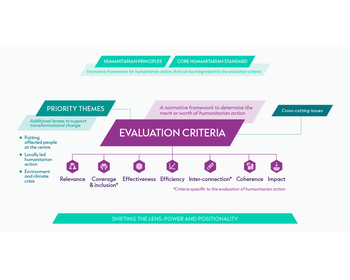

Evaluation criteria provide a normative framework to determine the merit or worth of humanitarian action.[5] In other words, they describe a comprehensive list of the desired attributes of humanitarian action, namely that it should:

- be relevant to the context and appropriate to those affected by crisis – relevance[6]

- reach those most in need – coverage and inclusion

- achieve desired results and avoid harmful consequences – effectiveness

- deliver results in an efficient way – efficiency

- be connected to other forms of development and peacebuilding activity, with a medium- to long-term perspective – inter-connection (formerly connectedness)

- be complementary, coordinated and consistent across humanitarian actors, aligning with policies and standards – coherence

- make a positive difference – impact.

Note, as described in Chapter 3, not all criteria will apply to every evaluation of humanitarian action. This is an exhaustive list from which those commissioning the evaluation should select.

The criteria are ordered deliberately. They put people affected by crisis centre-stage in evaluating relevance and coverage, then they consider the effectiveness and efficiency of programmes, then the more complex and systemic concepts of inter-connection and coherence, and they end with the wider and potentially transformative impact of humanitarian action.

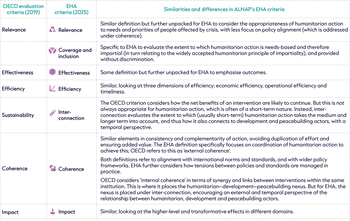

Some of these criteria align directly with the OECD criteria. For others, we have adapted and nuanced the definition to specifically suit humanitarian action. Two additional criteria are particularly important for EHA, building on the ALNAP guide (2006): coverage and inclusion, and inter-connection.[7] Table 1 summarises alignment and divergence between ALNAP’s EHA criteria and the OECD criteria.

Table 1: OECD criteria and ALNAP’s adapted criteria for EHA

The priority themes, as introduced in Chapter 1, provide an additional lens to evaluate humanitarian action. They complement the OECD criteria and offer opportunities for evaluation to enhance performance and also support transformational change, often at system level. The priority themes are:

- Putting people affected by crisis at the centre (linked to efforts within the humanitarian system to improve how humanitarian actors engage with affected people)

- Locally led humanitarian action (also referred to as localisation within the humanitarian system)

- Environment and climate crisis.

To varying degrees, these priorities are reflected as sub-themes within the OECD criteria. Consider giving explicit attention to some of these issues to generate more specific and relevant evaluation questions that, if answered, can drive substantial change. This is where evaluation can support transformational change.

At the same time, you may prefer to explore these themes within the existing criteria framework. In such cases, use the guide to inform more targeted questions and lines of enquiry within those criteria.

Table 2: EHA priority themes

Note, you may be asked to consider important cross-cutting issues throughout the evaluation process, and under a number (if not all) of the evaluation criteria. Different organisations may have their own cross-cutting issues to be considered in EHA. ALNAP’s EHA guide (2006) identifies eight cross-cutting issues.[8]We consider two in this guide:

- Inclusion: although now elevated to being part of the coverage criterion, inclusion can also be considered for all other criteria. It includes and goes beyond gender equality to consider other patterns of marginalisation and discrimination as well, and, as far as possible, their underlying causes.

- Adaptiveness/adaptive management: this is key to effective and relevant humanitarian action, given the dynamic and unpredictable nature of crises and the fast-paced nature of humanitarian action.

These cross-cutting issues are described in Annex 2, where they are applied to the criteria.

Figure 3 summarises the different elements of the guide.

Figure 3: Different elements of this guide

2.4: Shifting the lens: power and positionality

Chapters 4–10 discuss the seven EHA criteria in turn, and each includes a ‘Shifting the lens: power and positionality’ section. These sections explore how power dynamics and positionality shape evaluations and interpretations of criteria. They prompt reflection on what is evaluated, how and by whom – inviting shifts that enhance the fairness, accuracy and relevance of findings. Key examples are given, but there are many facets to addressing power and positionality that this guide does not cover. This requires ongoing reflection, adaptation and dialogue within each unique context.

Why is this important? Positionality shapes how you perceive the world and carry out evaluations, based on your social identities, experiences and affiliations – whether you are an evaluator, commissioner or programme staff. It affects which questions you ask, whose knowledge you prioritise, and how you frame and use findings. Crucially, positionality can introduce bias, often subtly – for example, by reinforcing dominant narratives or privileging certain voices over others. By recognising positionality and power, the guide invites you to shift your lens to uncover blind spots, challenge inherited assumptions and engage more equitably with diverse forms of knowledge in evaluation.

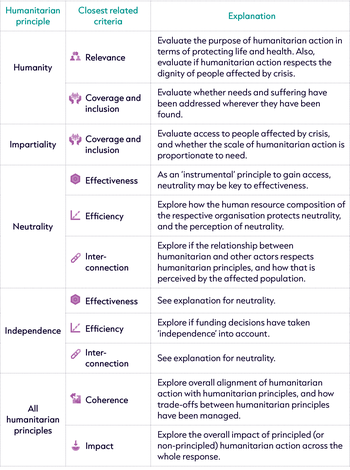

2.5: Relating the criteria to humanitarian principles

If the humanitarian actor that is the focus of the evaluation is committed to humanitarian principles as the ethical or even legal framework for its humanitarian action, these principles should be integrated into all standard evaluations of its humanitarian action. However, there is a poor track record in doing this.[9] Here, we explain how to integrate humanitarian principles within the framework of the EHA criteria.

How do humanitarian principles relate to ALNAP’s evaluation criteria?

Humanitarian principles do not map directly onto the EHA criteria. However, evaluation questions about the role of humanitarian principles in guiding decision-making and humanitarian action can usually be linked to one or other of the criteria

At the end of each chapter, this guide suggests how and where to integrate humanitarian principles within the framework of the evaluation criteria. Table 3 above provides a summary.[12]

Table 3: How the humanitarian principles relate to the criteria

2.6: A note on the Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS)

When evaluating an organisation that is committed to the CHS, these can also be mapped onto the evaluation criteria (CHS, 2024). See Annex 3 on the CHS and the EHA criteria.

Footnotes

-

See Annex 1 for a glossary of other useful terms.

-

This definition of humanitarian action is adapted from that in ALNAP (2016), to add and reflect the centrality of protection. As well as having their basic needs met, those affected by crisis also need protection – from violence, abuse, coercion and deprivation – and respect for their rights in accordance with the letter and spirit of relevant bodies of law (IASC, 2016).

-

This definition is drawn from ALNAP (2016).

-

See ALNAP (2016) for further explanation of some of these challenges and how to address them.

-

This is adapted from the OECD DAC definition – ‘A criterion is a standard or principle used in evaluation as the basis for evaluative judgement’ (OECD, 2021: 18) – in order for us to make a clear distinction with the priority themes.

-

In the 2006 guide relevance is combined with appropriateness. In this updated guide the two levels of analysis are maintained, but appropriateness no longer features in the name of the criterion.

-

However, the OECD (2021) acknowledges that, in humanitarian contexts, the additional criteria of appropriateness (folded here into relevance), coverage and connectedness may be highly relevant to evaluation.

-

The cross-cutting ‘themes’ in the EHA guide (ALNAP, 2006) are: local context; human resources; protection; participation of primary stakeholders; coping strategies and resilience; gender equality; HIV/AIDS; and the environment. Protection is now regarded as central to humanitarian action and is integrated throughout this guide. Some others now appear as priority themes or they are woven into this guide.

-

See UNEG (2024) and also UNEG (2016a), which find few references to humanitarian principles in evaluations of humanitarian action.

-

This includes the International Red Cross and Red Crescent movement, UN agencies engaged in humanitarian action, many international NGOs (INGOs) and some donor governments.

-

Humanitarian resistance has been described as the rescue, relief and protection of people suffering under an unjust enemy regime, by individuals and groups politically opposed to the regime. Thus, humanitarian resistance means taking sides. Solidarity is a commitment to unity and a common cause, which may mean ‘resisting’ enemy power. Once again, this means taking sides rather than remaining neutral (Slim, 2022).

-

When presenting evaluation findings on humanitarian principles, either interweave these findings throughout your final report or capture them in a specific chapter on alignment with humanitarian principles.