Priority themes

This chapter presents three priority themes and how to intentionally include them in evaluation of humanitarian action. The priority themes provide additional lenses through which to evaluate humanitarian action, and they complement the criteria (see Chapters 1 and 2 for the rationale and definition of priority themes).

11.1: Putting people affected by crisis at the centre

Key messages

- Humanitarian actors have committed to put people affected by crisis at the centre of humanitarian action, but deep-rooted power imbalances hinder how actors apply this in practice. Consequently, humanitarian action often fails to align with the needs and priorities of those who actors seek to assist.

- Pay particular attention to the quality of engagement, including cultural sensitivity and dynamics of power and trust between humanitarian actors and communities. Explore whether the perspectives of people affected by crisis have been listened to and acted upon.

- Put affected people at the centre in evaluation. Consider carefully who should be involved and for what purpose, how they will participate at each step of the evaluation process, and what benefits they reap.

Why it’s important

Humanitarian actors have long committed to put people affected by crisis at the centre, as emphasised in different standards and frameworks. Humanitarian actors should seek out and value the diverse knowledge and experiences of people affected by crisis. They should actively listen to understand what matters most to affected people and ensure that decisions are based on their needs and perspectives. It is especially important that humanitarian action recognises the inherent agency of affected people and that humanitarian actors understand, respect and build upon what people are already doing positively for themselves in a crisis context.

Many humanitarian organisations and evaluators continue to face challenges in ensuring they are led by the priorities of people affected by crisis. And this reflects fundamental and deep-rooted power imbalances within the humanitarian system (ALNAP, 2022; Doherty, 2023). Opportunities are missed for genuine community engagement; there is a lack of accountability to affected people; and humanitarian programmes, policies and measures of success do not fully align with the needs and priorities of those they aim to assist.

11.2: Intentional use of the priority theme in evaluation

Key areas of enquiry

Follow key areas of enquiry to evaluate the extent to which humanitarian action is driven by the priorities of people affected by crisis.

- Agency and decision-making: Evaluate the extent to which people affected by crisis have been able to influence decisions made by humanitarian actors throughout the response. Look for concrete ways that humanitarian actors have been led by or have responded to affected peoples’ preferences and priorities in a timely manner.

- Quality engagement and communication: Evaluate the nature of the relationship between humanitarian actors and affected people, and especially the different ways humanitarian actors have sought to listen to, and address, their concerns. This includes efforts to engage with diverse groups, such as youth, older people, women, children, persons living with disability and ethnic groups. Assess cultural sensitivity and dynamics of power and trust between humanitarian actors and communities, and the ways humanitarian actors have observed the principle to ‘Do No Harm’.

- Results and resources: Evaluate the extent to which the success of humanitarian action is judged by its effectiveness in involving affected people in decision-making and in responding to their concerns and feedback. Look for evidence that indicators of effectiveness have been identified by affected people as well as by humanitarian actors. Has community engagement been included as a specific outcome indicator, or prioritised by leadership? Have sufficient resources – funding, personnel and time – been allocated to facilitate meaningful participation of affected populations in decision-making processes?

- Coordination and collaboration: Review systems and partnerships between humanitarian actors put in place to better meet the needs of affected people and reduce the burden of data collection. Assess the extent to which humanitarian actors have shared data, coordinated communication efforts and engaged with communities. Have assessments been harmonised to minimise disruption and provide more coherent and accessible support to affected populations?

Source: This draws on several frameworks and guidelines, such as the CHS (2024). See also Annex 3.

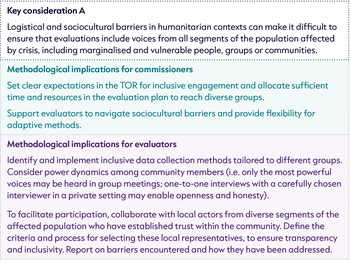

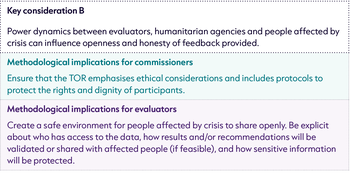

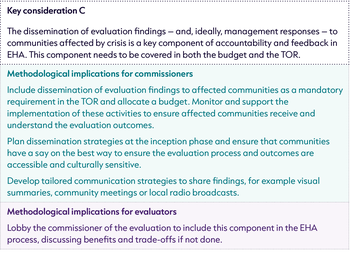

11.3: Methodological implications

11.4: Evaluation examples

11.5: Locally led humanitarian action

Key messages

- Evaluation is important to explore local actors’ leadership (or lack thereof) in humanitarian action. Analyse the structural and operational barriers that limit the influence of local actors and recommend how these can be overcome. Actively engage local actors in the EHA process to comprehensively understand humanitarian action.

- Local actors are not a homogeneous group; they operate with different priorities and relationships within their communities. Consider how these variations influence their ability to lead humanitarian efforts, how they relate to the population affected by crisis, and whether certain groups face barriers to participation or resources.

Why it’s important

Locally led humanitarian action ensures that crisis response is shaped by those closest to the affected population and their needs, and that action leverages local capacities and leadership. It strengthens existing community structures rather than bypasses them. For both local and international actors, this means aligning efforts with, and reinforcing, local systems. This means working with community structures on protection issues, partnering with local health clinics for medical support, and supporting disability-led organisations to ensure inclusive and accessible livelihoods.

It is crucial to recognise the diverse roles of local actors. Many are deeply embedded in their communities and well-positioned to respond to local needs, but their approaches and priorities can vary. It is especially important in conflict-related crises to understand how their positionality can influence who receives humanitarian assistance – and who is excluded. In some cases, local actors may exclude certain groups based on factors like ethnicity and/or they may have motivations other than humanitarian ones. Understanding how affected people perceive different actors is also critical. Integrate these perspectives in your evaluation (see Methodological implications below) to gain a more nuanced view of locally led humanitarian action and its impact on communities.

11.2: Intentional use of the priority theme in evaluation

Key areas of enquiry

Follow key areas of enquiry to evaluate locally led humanitarian action. Assess which areas of enquiry are most appropriate according to the nature of humanitarian action, key issues and challenges arising, and the scope and scale of your evaluation.

- Ownership, leadership and influence: Explore the extent to which humanitarian action is locally owned and influenced at all stages of the humanitarian response. If international support was available, examine if international humanitarian actors have supported local leadership. Consider variations in local actors' values, priorities and power dynamics, and how this shapes their leadership and relationships with affected communities (e.g. their role in the inclusion or exclusion of certain groups in receiving assistance).

- Knowledge and capacity exchange: Evaluate how all humanitarian actors promote knowledge and capacity exchange with each other, whether international or local. Assess whether knowledge-sharing is reciprocal or one-directional, the extent to which capacity support is demand-driven, and how well it aligns with local priorities.

- Funding: Investigate the quantity and quality of humanitarian funding directed towards local and national actors from different sources – international and national. Analyse the flexibility, adequacy and duration of funding, and whether it adequately supports overhead costs and risks faced by local actors.

- Partnerships: Evaluate the quality of partnerships between local actors (e.g. local organisations often forge partnerships with other local actors such as community-based organisations), and between international and local actors. Assess how these partnerships are formed, negotiated and maintained, and the extent to which they foster equitable collaboration, risk-sharing and mutual respect.

- Visibility and recognition: Examine how humanitarian action contributes to increasing the visibility and recognition of local actors' work in the response. Evaluate if local actors are acknowledged publicly in ways they deem appropriate and that do no harm, and how their role is represented in reports, media and policy discussions.

- Coordination and complementarity: Examine the extent to which humanitarian coordination mechanisms promote and reinforce local leadership, including organisations and groups representing the marginalised and vulnerable. Analyse whether humanitarian action builds on existing coordination mechanisms between local actors.

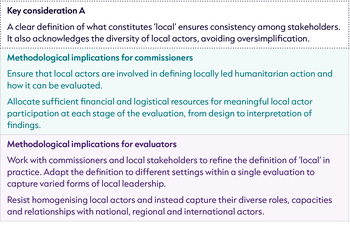

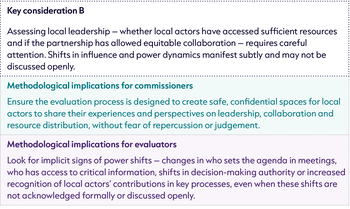

11.3: Methodological implications

11.8: Evaluation example

11.9: Environment and climate crisis

Key messages

- EHA can capture the consequences of the climate crisis on the humanitarian system, and also show how humanitarian action contributes to or mitigates this crisis.

- When evaluating how humanitarian action takes account of the environment and climate crisis, explore how local and/or Indigenous knowledge, practices and solutions have been considered.

Why it’s important

Man-made environmental degradation is driving interlinked crises, including the climate crisis, biodiversity loss and the spread of infectious diseases (Chaplowe and Uitto, 2022; Hauer and Wahlström, 2023). Droughts and floods brought about by the climate crisis can significantly increase humanitarian needs by contributing to displacement, instability and violence.

In line with the principle to ‘Do No Harm’, it is increasingly important to consider environmental factors in humanitarian action and efforts to minimise negative environmental impacts. EHA can provide evidence on the consequences of the climate crisis on the humanitarian system, and support learning on mitigation measures. EHA can also hold the humanitarian system to account if/when actions contribute to the climate crisis.

Consider including the environment and climate crisis in evaluations, even when these aspects are not addressed explicitly in humanitarian action.

11.2: Intentional use of the priority theme in evaluation

Key areas of enquiry

Follow key lines of enquiry at different levels. Since progress still needs to be made in regularly integrating the environment and climate crisis into humanitarian action, a first step is to evaluate if any environmental mitigation measures have been planned and implemented.

- Organisational level: Explore if an organisation-wide policy or strategy is in place on the environment and climate crisis, if there is an environmental management system and associated action plan, and the extent to which these are applied in practice (Hauer and Wahlström, 2023).

- Humanitarian response level: Depending on context, explore water use management, waste management, reduction of carbon emissions, choices of energy solutions, and/or whether the humanitarian response has taken measures to protect habitats and their inhabitants. Consider if the humanitarian response minimised environmental damage to areas affected by crisis, in terms of deforestation, biodiversity loss and the degradation of natural resources (Haruhiru et al, 2023). Have day-to-day operational management decisions protected the environment – such as in the supply chain, fleet management, travel, and information and communication technology? The environment and climate crisis is particularly important in WASH, shelter and food security, and livelihood programmes, and in logistics and human resources. Remember environmental effects and actions taken to reduce them are often context-specific.

- Local and/or Indigenous knowledge and practice: Evaluate if the design and implementation of the humanitarian response have considered local and/or Indigenous knowledge and practice. Has humanitarian action adapted to the local context, and has it valued and integrated local and Indigenous solutions? Local actors have in-depth knowledge of their environments and may deliver more environmentally sustainable assistance (Haruhiru et al, 2023).

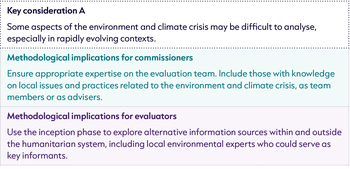

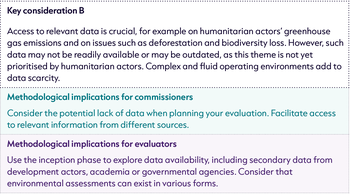

11.3: Methodological implications

11.8: Evaluation example

Footnotes

-

Talanoa is ‘a personal encounter where people story their issues, their realities and aspirations’. This approach ‘allows more mo’oni (pure, real, authentic) information to be available for Pacific research than data derived from other research methods’. See Vaioleti (2006).