Relevance

Key messages

- Centre your evaluation of relevance on understanding the needs and priorities of different groups and communities within the population affected by crisis, and how/if these needs and priorities have informed the design and implementation of humanitarian action.

- Your positionality as an evaluator influences how you understand, interpret and prioritise the needs and priorities of different stakeholders. Reflect on how different factors such as cultural background and organisational affiliation influence your judgement.

4.1: Explanation of definition, and how to use this criterion

Explanation of the definition

The relevance of humanitarian action may be evaluated at macro and micro levels (where it is also referred to as appropriateness). The macro level refers to what – evaluation of the overall objectives or purpose of humanitarian action; the micro level refers to how – evaluation of the type and mode of assistance, including inputs and activities.

Unpack and interrogate the logic or theory of change of the humanitarian response. For example, decreasing morbidity and mortality may be a relevant overall objective for humanitarian action, but strengthening the quality of secondary health care in an area by staffing and rehabilitating a hospital might not be appropriate to achieve this objective. It might be more appropriate to strengthen primary health care structures, engaging with Indigenous health care providers, or to simply facilitate people’s access to existing structures by providing transportation.

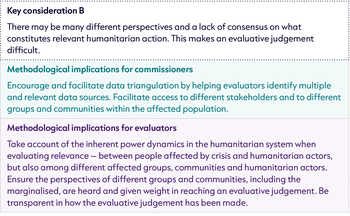

Analyse the context and explore the different needs and priorities of people affected by crisis. Review any needs assessments that have informed the design of the response. As highlighted in the OECD definition, consider that there might be potential tensions between the needs and priorities of affected people and those of other stakeholders, such as humanitarian responders and institutional partners. There may be some tensions between the short-term nature of humanitarian action and people’s long-term needs for stability and to rebuild their lives. For example, a humanitarian actor might prioritise building latrines for a community affected by crisis to meet international standards, but community members put greater value on the building of schools. There might also be tensions between the needs and priorities of different groups and communities within the population affected by crisis, meaning that trade-offs have been made. What is of value for one stakeholder or group might not be of value to others. Explore these tensions and the implications of the choices made (OECD, 2019, 2021; Darcy and Dillon, 2020).

Explore if issues related to the environment and climate crisis have been considered in the design and implementation of humanitarian action. Were the environmental context and the environmental knowledge and practices of people affected by crisis considered to deliver relevant assistance? This is further explained in section 11.3 Environment and climate crisis.

Also explore how conflict-related factors have affected the relevance of humanitarian action. For example, certain types of humanitarian assistance may be irrelevant at local level if they leave people more vulnerable to attack. In some contexts, a household may become a target if livestock is restocked where there is a high risk of looting by militia or if cash is distributed. This is conflict-insensitive programming and it fails to respect the principle of ‘Do No Harm’, with negative consequences for protection.

As an aspect of relevance, evaluate participation and ownership by key stakeholders – especially people affected by crisis – in the design and implementation of humanitarian action. What is the nature of the overall relationship between humanitarian actors and affected people and how has this relationship influenced the relevance of the response? How were needs assessments and other assessments conducted? Were key stakeholders, including affected people, involved in designing the humanitarian response? What feedback channels were there to ensure continued relevance? Also evaluate the role of local actors in the design of the humanitarian response. How satisfied are local actors with their level of involvement and influence in shaping the purpose and activities of the response? These aspects can help explain why humanitarian action is or is not relevant. This is further explained in section section 11.1 Putting people affected by crisis at the centre.

When to select relevance

Relevance should be widely used as an EHA criterion to understand if humanitarian action has been designed and implemented to do the right things to respond to need. Irrelevant assistance could have severe and harmful consequences for the well-being of people affected by crisis.

How relevance relates to other criteria

When relevance is combined with coverage and inclusion, the evaluation explores whether humanitarian action is doing the right things for the right people, i.e. those in greatest need. When relevance is combined with effectiveness, the evaluation provides an overview of what has been achieved and how well, and also if humanitarian action is doing the right things.

Humanitarian action might be highly effective in achieving the desired results set out in a funding proposal, but irrelevant to the needs and priorities of people affected by crisis. For example, if protection risks and needs have been ignored in the design and implementation of humanitarian action, an evaluation focused on effectiveness might draw different conclusions to one focused on relevance and effectiveness (ALNAP, 2018).

4.2: Shifting the lens: power and positionality

Exploring relevance through the lens of power and positionality asks you to consider: How does your positionality as an evaluator shape your assumptions about whose needs matter? How might your line of evaluation questioning reproduce power imbalances or silence alternative viewpoints on what constitutes the ‘right’ needs, knowledge or solutions?

For example, when reporting whether humanitarian action is relevant, examine whether your conclusions reinforce paternalistic narratives – such as framing people affected by crisis solely as passive recipients of humanitarian assistance – and diminish local agency or leadership in shaping responses.

Shifting the lens could also mean that triangulation compares data sources and also actively interrogates divergences in perspectives between local actors, community members and external stakeholders.

4.3: Methodological implications

See Chapter 11 for further methodological implications, particularly key considerations related to putting people affected by crisis at the centre.

4.4: Evaluation examples

Humanitarian principles and relevance

This is an opportunity to evaluate the principle of humanity, which is the purpose of humanitarian action: to protect life and health. How well do humanitarian actors understand the needs and priorities of people affected by crisis in order to achieve this purpose? Relevance relates closely to the principle of impartiality too, prioritising assistance according to need.

Humanity is also about ensuring respect for human beings. In evaluating relevance, look for evidence that humanitarian action and the modalities of assistance do indeed respect and promote the dignity of those affected by a crisis. Pay attention to the nature of the relationship between the respective agency(ies) and affected people. For all lines of enquiry, it is essential that you listen to the perspectives and experience of affected people.

Example evaluation question:

To what extent was assistance provided according to the needs and priorities of people affected by crisis, in ways that respected their dignity, according to the principles of humanity and impartiality?

Footnotes

-

In 2006, ALNAP combined relevance with appropriateness; in this updated guide the two levels of analysis are maintained but appropriateness no longer features in the criterion’s name.

-

The OECD definition of relevance also includes policy alignment which, in this guide, is covered under coherence.