It has been over three years since humanitarian donors and implementers signed the ‘Grand Bargain’, promising to make aid more focused on, and responsive to, the people it is supposed to serve. Has the sector been true to its promise? At Ground Truth Solutions, we talked to the real experts about humanitarian aid to see if quality is improving – the people affected by crisis and field staff serving them.

Since 2016 we have been tracking progress of these commitments, along with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), through the first-hand experience of some 5,000 affected people and 1,500 aid providers.

We asked people across seven countries in 2018/9 (and six countries in 2017/8) questions to distinguish whether there has been a shift from what the Grand Bargain describes as a supply-driven model dominated by aid providers to one that is more demand-driven. Do people affected by crisis see humanitarian organisations going beyond meeting their basic needs? Do they feel they could be self-reliant and have opportunities to live without aid, even in protracted crises and facing recurring vulnerabilities?

Here’s what we learned from respondents in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Iraq, Haiti, Lebanon, Uganda and Somalia:

1. People feel safe and treated with respect by aid providers

Consistently across countries and contexts, people who have received humanitarian aid say they feel mostly safe in their place of residence. They also feel treated with respect by aid providers who, they do believe, have their best interests at heart.

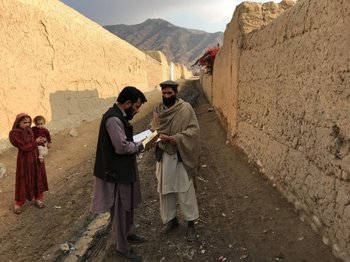

Ground Truth Solutions partner interviews a family in Afghanistan, December 2018. Photo credit: Ground Truth Solutions

2. Much of the aid provided does not meet priority needs

As in previous years, about half of the people surveyed do not feel the aid delivered meets their most important needs, let alone enables self-reliance, as the Grand Bargain aims to achieve.

3. Cash, food and health services are the top unmet needs

The needs listed as unmet in most countries changed from last year, showing that what people consider to be unmet is context-dependent and dynamic. It also shows how important it is for people delivering aid to monitor the relevance of their programmes as they are implemented, and ensure they are based on an ongoing dialogue with affected communities.

4. Affected people are largely satisfied with cash assistance, while humanitarians seem slightly less enthusiastic about it

Satisfaction with cash assistance has grown over time amongst people affected by crisis. Although humanitarian staff remain positive about cash assistance, their enthusiasm has decreased slightly since 2017.

5. Most people do not feel self-reliant

Most people find aid ‘not at all’ or ‘not very’ empowering. This question repeatedly provokes some of the most negative responses in our survey. A male refugee we interviewed in Uganda said, "The food being given is not enough and the land I have is not fertile, so I am dependant on the UN forever."

6. There is some progress on the participation revolution, from a low base

More people (41%) say aid providers take their opinion into account than before. Scores in Somalia, Afghanistan and Bangladesh are positive, but there is still substantial room for improvement, especially but not only in Lebanon.

7. Feedback mechanisms are less effective than humanitarian staff think

While staff strongly believe that if people make complaints or suggestions, they will receive a response from their organisation, affected people who have filed complaints or made suggestions say they rarely hear back. Typically only just over half of affected people know how to make suggestions or complaints to agencies in the first place. The preferred methods are still face-to-face communication. In contrast, humanitarian organisations tend to prioritise hotlines.

8. There has been little change in how affected people view aid

By and large, affected people haven’t seen any difference in the aid they receive since last year. Haiti is the exception, with strong improvements, but only compared to dramatically low scores in 2017.

What next?

With the Grand Bargain in its fourth year, there is a need to shift the focus from policy discussions at a global level to tracking the impact of commitments on the ground. Grand Bargain workstreams have recently developed indicators to measure progress. These should be paired with systematic monitoring of affected people’s perceptions of improvement, to test whether those who are intended to benefit from better aid see progress. Similarly, when tracking strategic goals of Humanitarian Response Plans in countries, people’s views of success should be taken more systematically into account.

For more, visit www.groundtruthsolutions.org/grandbargain