At ALNAP’s 2019 Annual Meeting we wrestled with the challenges of ensuring that humanitarian responses meet the diverse and evolving needs of people in crisis. How, where and when financing is provided is key to this, and the Grand Bargain initiative explicitly recognises the need to realign how humanitarian assistance is provided in order to meet this goal.

Development Initiatives (DI) has provided annual analysis on how, where and by whom humanitarian assistance is contributed for almost 20 years. The 2019 Global Humanitarian Assistance report throws light on some of the key elements of the discussion that we had at the Annual Meeting, in particular on the role of financing in enabling adaptiveness, choice and co-design.

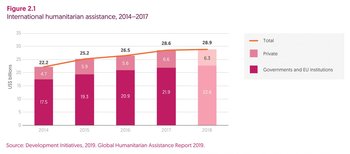

Firstly, however, it’s helpful to reflect on just how vital financing is. International humanitarian assistance grew by 30% over the past five years but this growth is slowing, with a combined increase of assistance from public and private donors of only 1% in 2018. While funding has grown, so has need – and in 2018 only 61% of the requirements of UN appeals were met. It is the same relatively small group of donors that are contributing, with more than 50% of all assistance from governments in 2018 coming from just three donors: the US, Germany and the UK. The channels through which funding is delivered have not altered either, with just under two-thirds of government funding going to multi-lateral organisations, and the majority of private funding going to NGOs. So, the trends we identified from 2015 to 2017 with ALNAP for their latest State of the Humanitarian System Report continued through 2018: while funding has increased, it is in many ways a relatively static picture.

Providing funding that is flexible and predictable – and also of sufficient quantity – is key in enabling responses to adapt to the needs of those affected by protracted crisis. When it comes to changes in how assistance is delivered, though, our analysis paints a mixed picture. Collecting data directly from nine UN agencies, we found that they reported receiving a decreasing proportion of their funding as unearmarked in 2018 – 17%, compared with 20% in 2015. On the other hand, multi-year funding, which can give greater predictability to meet longer-term and changing need in protracted crisis settings, appears to have risen as a proportion of all funding from donors – from 32% in 2016 to 37% in 2018. These types of funding are often seen as interconnected and complementary (as recognised in the recent merging of the Grand Bargain workstreams on unearmarked funding and multi-year funding). However, as DI and the Norwegian Refugee Council found in forthcoming studies on multi-year funding in Jordan and Lebanon, while agencies did report receiving more multi-year funding, many perceived that its value in allowing them to adapt programming was being undermined by increasingly tight restrictions – a trend also noted in ALNAP’s research on flexibility and adaptiveness in humanitarian settings.

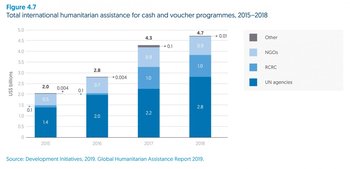

What can be said then of funding that can enable choice and co-design? Cash-transfer programming, while not suitable in all contexts, can give those in need greater choice – interviews that we conducted with people living in crisis in Somalia, for example, showed that recipients were better able to diversify their income and build resilience to crisis. Our analysis of international humanitarian assistance shows that progress is being made: cash-transfer programming grew by 10% in 2018 to US$4.7bn. However, as Ground Truth Solutions’ research on humanitarian cash programming has found, there is more to be done to improve the meaningful participation of recipients in the assessment, design, implementation and monitoring of cash programming.

The empowerment of local and national actors – those closest to a crisis – is critical to co-design and ensuring that responses best meet need. From a financing perspective, there are significant gaps in the available data. What we can see suggests that much more needs to be done to fulfil the humanitarian community’s commitments to localisation. Funding passing directly to local and national actors grew very slightly in 2018, accounting for 3.1% of all international humanitarian assistance (compared to 2.9% in 2017 and 2% in 2016, as reported in the SOHS 2018). There’s not enough reporting to form a clear picture of funding passed through an intermediary, but where we have collected data directly at the country level with Oxfam, total direct and indirect funding was less than 10% – far short of the 25% Grand Bargain target.

Fundamentally, meeting the priority needs of those affected by crisis requires sufficient volumes of funding, and we remain short in this regard. Beyond this, there are some encouraging signs that how assistance is provided is improving – but much more needs to be done, and more quickly. In this regard, developments in anticipatory and risk financing – highlighted in the 2019 GHA Report – that draw resources from the banking and insurance sectors to put financing in place to respond quickly, and in some cases in advance of a crisis striking, are particularly interesting. Meanwhile, the momentum and interest behind efforts to finally get to grips with the humanitarian-development-peacebuilding nexus – as evidenced by the recently agreed OECD DAC Recommendation – offer hope that immediate and long term needs of those affected by crisis, as well as the factors driving crisis itself, may be more effectively met and addressed.