In 2016, world political leaders along with NGOs, civil society figures, academia and private sector institutions held the first World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) to discuss the world’s crises and to innovate on new ways of addressing them.

The WHS concluded with initiatives to boost the collaboration and coherence of humanitarian response, development, and peace processes to end human suffering and ensure durable solutions, under the so-called ‘triple nexus’.

While actors from the three domains are striving to harmonise their approaches, the ongoing Syria crisis calls into question the reliability of the triple nexus as an approach. Contrary to the WHS commitments, Syrians are becoming increasingly vulnerable, and affected people are stuck in a devastating environment facing various risks and obstacles to survive.

Never-ending aid and rooted need

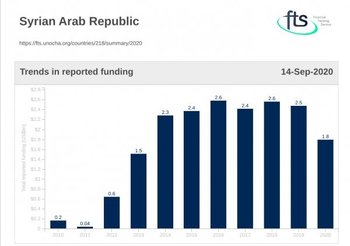

Two core commitments have failed in the Syrian context. One of them is From Delivering Aid to Ending Need. During the past ten years, the humanitarian sector has invested more than 14 billion USD in response to the Syria crisis which equals more than 1.5X the general budget of Syria for 2020 stated by the government.

Undoubtedly, this aid reached millions of internally displaced people and Syrian refugees in the neighbouring countries and helped them cope with the devastating consequences of war. However, the aid has not resolved fundamental needs in Syria. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 11 million Syrians still require humanitarian assistance, including 6.1 million IDPs.

The latest report by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) and the University of St. Andrews states that around 83.4% of the Syrian population lives below the poverty line. The situation has worsened since May this year due to the continuous inflation of the Syrian pound, which fluctuates on a daily basis between 2,200 and 3,000 to the USD in the informal market, leaving the average monthly salary between 15 to 22 USD, which is roughly around 3% of a family breadwinner’s income before the war started, and only enough to buy food to feed a small family for around five days.

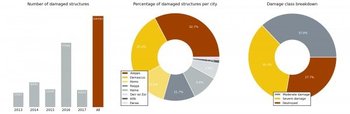

Moreover, the level of destruction in Syria is still not fully assessed. UNOSAT (UNITAR’s Operational Satellite Applications Programme) conducted a comprehensive damage assessment of eight of Syria’s largest cities between 2013 and 2017, and the results indicate massive destruction and need for scaling up rehabilitation work (see summary below).

Overview of damage assessment of eight of Syria's largest cities. Credit: UNOSAT

The continued catastrophic situation makes one wonder about the actual validity and operationalisation of the humanitarian-development nexus in the Syrian context and the vision beyond the applied programmes and strategies. Relief organisations are mostly governed by mandates designed for short-term/life-saving purposes, and in a protracted crisis, humanitarian aid may cause the adverse long-term impact of creating dependency on aid. While development projects require a secure and stable environment to take off and flourish, in armed conflicts they are stifled before starting.

However, many of Syria’s cities and rural areas are secure and without conduct of hostilities. In such areas, there has been an opportunity to start rehabilitation of infrastructure, public health facilities and services, markets, schools, and housing. This should have led to a restoration of livelihoods and boosted economic growth. Yet, development projects in Syria remain small in scale and function as patchwork rather than addressing the roots. Why is there a lack of large-scale development projects in safe and secure locations? What is the meeting or transition point between the two domains? What is the role of politics in launching long-standing interventions to change people’s lives?

Political contest worsening people’s lives

Another failed core commitment of the WHS is Political Leadership to Prevent and End Conflicts and Changing People’s Lives. The complexities of the situation in Syria have to be acknowledged to this extent, most importantly the continuous failure to broker a peace agreement between the national parties to the conflict, as well as the vigorous competition of different regional and global powers for the lion’s share, including the United States, Russia, Turkey, Iran, and some Gulf countries.

However, the continuous expansionist sanctions regime is imposed by the biggest donors of humanitarian aid (i.e. USA & the EU). Even though the sanctions are aimed at the Syrian authorities, the civilian population is the real victim as the economic situation steadily deteriorates. Moreover, private companies and investors increasingly end their businesses in Syria fearing the sanctions’ impact, shutting down any initiative towards recovery.

Photo credit: EC/ECHO

The overwhelming measures also result in the blockage of formal international transfers, which means that Syrians abroad, both refugees and immigrants, cannot send remittances to their families back home. By shutting down any opportunity to kick off the recovery phase and start a sustainable intervention, life-saving humanitarian relief serves as a short-term survival hook for the affected population with increased dependency on it.

Triple Nexus or Triple Paradox?

Although the concept of the triple nexus is promising, it is closer to a fairy tale. How would life-saving actors survive in protracted crises and remain efficient? Do they invest in the right place to alleviate and eradicate people’s suffering? How would development actors operate in hostile contexts? How can actors working within the humanitarian-development nexus match their plans? Would they need to adjust their mandates? Is it relevant to have a humanitarian-development nexus considering all these challenges?

As peace processes are essential to ending armed conflict, should we incorporate them in humanitarian and development operations? How would humanitarian action remain principled? Could development agencies invest in areas controlled by the donors’ enemies?

The Syria crisis shows that these questions have not been resolved in an operational context. Despite triple nexus talk being very present in meetings and global conferences, at HQ level it has hardly been applied in operations. A first step to resolve this may be contextualised research on an operational level to explore limitations and opportunities for piloting humanitarian-development operations. This may lead to developing context-specific plans which are neutral, independent, and free from political influence where possible. But are those realistic and doable suggestions to make the triple nexus work? Or is it an illusion in a highly politicised world?