Executive summary

The Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2025 shows a humanitarian sector entering financial crisis. Cuts in international humanitarian funding by many of the top government donors in 2024 delivered the biggest drop ever recorded. With further reductions announced for 2025, the public funding available for humanitarian action could contract by between 34% and 45% by the end of the year compared to 2023 levels. Reforms to increase effectiveness, such as funding to local and national actors and anticipatory action, have also seen stagnation and reversal – a trend that upcoming cuts may serve to accelerate if left unchecked. Countries experiencing protracted crisis are more vulnerable than ever; humanitarian assistance has overtaken development assistance as their dominant source of external concessional support, and the average protracted crisis pays double the amount in debt payments compared to a decade ago. This leaves serious questions about how they can find sustainable pathways out of crisis. A ‘humanitarian reset' announced by the United Nations’ Emergency Relief Coordinator reflects a sector facing up to this new and unprecedented challenge.

About this report

The Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) report is the world-leading annual assessment of the state of international humanitarian financing. Produced by Development Initiatives for 25 years and now by the ALNAP Network,[1]the GHA report provides a critical body of evidence to inform the sector about its financial size, how its finances are distributed, and what key trends require our focus if we want to protect and improve the funding response to crisis.

Global humanitarian assistance is defined as the total international financial resources available for humanitarian action and comprises public funding from government donors alongside private funding from sources such as philanthropy and individual giving.

The GHA Report 2025 sets out the scale and nature of disruption affecting humanitarian funding, providing a critical tool for navigating an unprecedented moment of political and economic change. Humanitarian action faces a “crisis of legitimacy, morale and funding”.[2] Escalating geopolitical tensions, economic stagnation and rising debt mean the humanitarian responsibilities that once received wide support are being abandoned, as many countries prioritise security and competition over multilateralism and shared norms. Meanwhile, low- and middle-income countries seek equitable partnerships, rejecting outdated paternalistic models of aid, and crises fuelled by conflict, climate emergencies and economic instability continue unabated. Against this backdrop, the humanitarian sector has entered a period of high turmoil, with calls for a humanitarian reset[3] and related reforms to respond to this moment with a new vision and approach.

Funding trends

Humanitarian financing fell by 10% in 2024, before the cuts announced in 2025

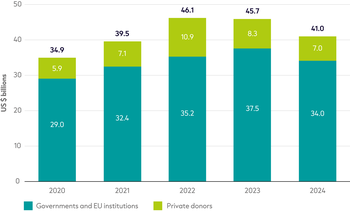

Total international humanitarian assistance, 2020–2024

Source: ALNAP based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC), UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS), UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and our unique dataset for private contributions.

Notes: Figures for 2024 are preliminary. Totals for previous years differ from those reported in previous GHA reports due to updated deflators and data. Data is in constant 2023 prices. The methodology used to produce total international humanitarian assistance is detailed in the ‘Methodology and definitions’ chapter.

This figure was revised on 29 July 2025.

Record cuts began in 2024, reversing over a decade-long upward trend. International humanitarian assistance fell by 11% – nearly US $5 billion – in 2024, the largest cut ever recorded. This marks a clear departure from the trend since the early 2010s of steady and substantial commitment to humanitarian funding, which had seen volumes double between 2011 and 2017, climbing to a peak of US $46.1 billion overall in 2022. These cuts were driven by 16 of the 20 largest donors reducing their humanitarian funding alongside a smaller but notable fall in private contributions.

This unprecedented reduction means that the humanitarian sector experienced a significant funding shock even before aid cuts from major donors in 2025. Reliance on a relatively small number of large donors has always made the system vulnerable to shocks. Now, with the political context shifting dramatically for many donor countries at once, the impact is potentially catastrophic.

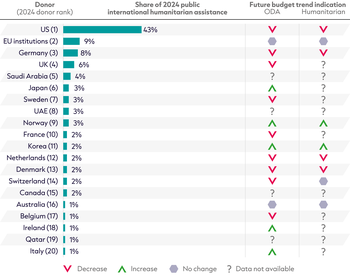

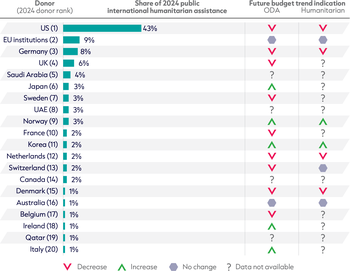

The majority of top donors cut humanitarian funding in 2024

20 largest public donors of humanitarian assistance in 2024, and change from 2023

Source: Based on OECD DAC, UN OCHA FTS and UN CERF.

Notes: 2024 data is preliminary. Data is in constant 2023 prices. ‘Public donors’ refers to governments and EU institutions. 2023 figures differ from the 2024 Falling short report[4] due to final reported international humanitarian assistance data and a different year for constant prices. UAE = United Arab Emirates.

This figure was revised on 29 July 2025.

The majority of donors providing international humanitarian assistance reduced funding in 2024. The largest cuts in volume terms came from the United States (−US $1.7 billion; −10%), Germany (−US $0.8 billion; −23%) and EU institutions (−US $426 million, −13%).

However, the shape of the funding landscape has not shifted overall. The top 10 donors still provided 84% of all public humanitarian assistance in 2024, compared to 83% in 2023. Private donors[5] contributed an estimated US $7.0 billion in 2024, down from US $8.3 billion in 2023 (and down by over a third from the peak in 2022).

Humanitarian funding cuts

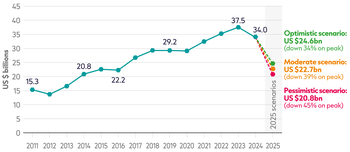

Funding from governments could drop by 34% to 45% in 2025 from its peak in 2023

Three scenarios for humanitarian funding from public donors in 2025

Source: Historic data based on OECD DAC, UN OCHA FTS and UN CERF. 2025 scenarios are based on publicly available information regarding ODA or humanitarian budgets.

Notes: 2024 data is preliminary. Data is in constant 2023 prices. ‘Public donors’ refers to governments and EU institutions. Historical figures differ from the 2024 Falling short report[6] due to final reported international humanitarian assistance data and a deflation. Methodological notes on how the 2025 scenarios were constructed are detailed in the ‘Methodology and definitions’ chapter.

Deeper cuts in 2025 could see humanitarian assistance from government donors drop by nearly a half (45%) by the end of the 2025 compared to the peak reached in 2023. While scenarios must be taken with caveats,[7] based on donor announcements made through April 2025 it is possible to assess the potential volume of cuts coming in 2025. The optimistic scenario is that funding will fall by over a third (34%) by the end of 2025 compared to peak funding levels in 2023. The pessimistic scenario sees a reduction in funding from government donors of almost half (45%), which would put the sector back by a decade to 2014 funding levels from public donors.

Almost half of the largest 20 humanitarian donors announced cuts to their future aid spending, including three of the top four

Changes in ODA and humanitarian assistance budgets for the 20 largest donors of international humanitarian assistance, 2025

Source: Authors based on Donor Tracker data, press reports and government budget documents.

Notes: Sweden’s ODA in 2025 remains stable compared to 2024 levels, however a decrease is indicated in the table because the Swedish government has decided to cut ODA by 5% for 2026–2028. Directional arrows indicate any trend in budget as per sources, regardless of the magnitude of the increase or decrease. A question mark denotes that the trend is unknown. UAE = United Arab Emirates.

This figure was revised on 29 July 2025.

The outlook for humanitarian financing is bleak, with almost half of the top 20 humanitarian donors announcing cuts to their ODA budgets for 2025. This includes three of the top four humanitarian donors. However, there is still a large degree of uncertainty regarding the impact on the humanitarian sphere. High-level announcements do not always have the sufficient detail regarding humanitarian spend versus the rest of ODA, and some budgetary decisions are yet to be agreed.

Parts of the humanitarian system are greatly exposed to the cuts coming from donors. This includes specific countries – 10 of the top 30 recipients of humanitarian assistance received more than 70% of their funding from donors that have announced cuts – as well as specific humanitarian sectors, including nutrition and food security and agriculture, which both relied on the United States for over half of their funding. UN agencies are also at risk, with humanitarian funding to the World Food Programme, International Organization for Migration, Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East dependent to at least 60% on the donors that have announced cuts. In protracted crisis contexts, specific development sectors are particularly reliant on donors that have announced cuts to funding, including the government and civil society sector, which is 92% funded by these donors.

Humanitarian reform

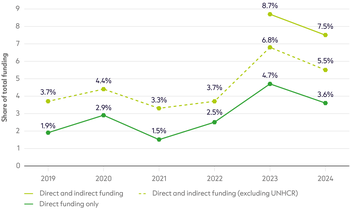

The share of international humanitarian assistance to local and national actors fell in 2024

Proportion of direct and total (direct and indirect) funding to local and national actors, 2019–2024

Source: Based on UN OCHA FTS.

Notes: 2024 is the second year the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has published granular data on its partnerships that can be independently verified against the Grand Bargain definitions of local and national actors, making only a direct comparison with 2023 possible. Comparisons across a longer period are done by excluding UNHCR.

There has been backsliding on commitments for reforms to improve the effectiveness of humanitarian funding. Direct and indirect funding to local and national actors[8]fell to just 7.5% of total assistance in 2024, and cash and voucher assistance[9] fell both in volume terms (by 15%) and as a proportion of total international humanitarian assistance. Funding for anticipatory action[10] stagnated in 2024 despite around one-fifth of humanitarian response needs being as a result of highly predictable shocks.

Donors have struggled to deliver on commitments for reform made back in 2016 as part of the Grand Bargain,[11] and 2024 saw even further backsliding. There is a clear risk that the cuts coming in 2025 will only serve to accelerate these trends as donors grapple with upheaval in their budgets.

Beyond humanitarian funding

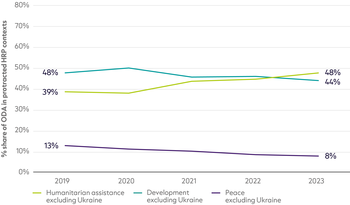

Humanitarian funding now outgrows development funding in protracted HRP contexts when Ukraine is excluded

Share of ODA to development, humanitarian, peace and climate from DAC donors to protracted HRP contexts, excluding Ukraine

Source: Based on OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Notes: Recipients vary between years. Data is in constant 2023 prices.

Humanitarian assistance overtook development assistance for the first time in 2023 as the dominant source of external concessional support for countries experiencing humanitarian crisis for five years or more. Increases in funding from multilateral development banks to crisis contexts have also stalled, returning back to pre-pandemic levels in 2023.

The average protracted crisis context is now paying double on government debt payments in 2024 than a decade ago. Every dollar spent servicing debt is one less dollar available to provide basic services that can reduce crisis risk and support recovery.

Looking ahead

We are entering a new era for international humanitarian response. After 15 years of overall growth in humanitarian assistance, donors are rolling back support. Shifts in the political landscape in many donor countries have created a difficult environment for the aid sector that has not been seen before.

Humanitarians now face tough short-term operational decisions alongside the need for strategic longer term shifts to respond to the impacts of this new reality. At the operational level this means cutting costs through workforce reductions and potential agency mergers; narrowing geographic and thematic focus to prioritise the most critical needs; and scaling back or redefining existing programmes due to limited resources. At the strategic level, the mooted humanitarian reset is focusing on maximising crisis responses with current resources, reforming operational approaches, and shifting power to local leaders and affected communities. Alongside it, the Grand Bargain is exploring efficiency and structural reforms.

The two major questions that must now be answered are: how should the sector change its approach to mobilise new and additional funding for humanitarian action in this new global context? And if the system needs to reform, or transform, to meet the needs of affected populations – regardless of the funding level – what does it prioritise?

Figures 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4 and 3.1, equivalent figures in the Executive summary, and analysis on pages viii, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 35 were revised on 29 July 2025 to reflect corrections provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark correcting an error in IHA as reported to OECD DAC.

Footnotes

-

Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in humanitarian action.

-

UN OCHA, 2025. The Humanitarian Reset, Letter from Tom Fletcher, Chair of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, UN Under-Secretary- General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator. Available at: https://www.unocha.org/news/humanitarian-reset

-

UN OCHA, 2025. The Humanitarian Reset, Letter from Tom Fletcher, Chair of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, UN Under-Secretary- General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator. Available at: https://www.unocha.org/news/humanitarian-reset

-

Development Initiatives, 2024. Falling short? Humanitarian funding and reform. Available at: https://alnap.org/help-library/resources/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2024/

-

Our private funding calculation comprises an estimate of total private humanitarian income for all non-governmental organisations and the private humanitarian income reported by UN agencies, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

-

Development Initiatives, 2024. Falling short? Humanitarian funding and reform. Available at: https://alnap.org/help-library/resources/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2024/

-

Calculations are based on data and information available relating to aid cut announcements by donors up to and including May 2025.

-

Funding to local and national actors ensures it goes to organisations that have vital local knowledge, networks and cultural understanding, giving them a uniquely important role in ensuring effective humanitarian response.

-

Cash and voucher assistance is quicker, more flexible and offers greater dignity for people affected by crisis.

-

Anticipatory action reduces the humanitarian impacts of a forecast crisis before it occurs, or before its most acute impacts are felt.

-

An agreement to reform the delivery of humanitarian aid that was proposed at the World Humanitarian Summit in May 2016.