Humanitarian finance in the age of cuts

3.1: Overview

The immediate direction of travel for the humanitarian sector is clear – the decrease in funding in 2024 will continue into 2025 and most likely beyond. As of June 2025, nine of the top 20 humanitarian donors have announced cuts to their official development assistance (ODA), including three of the four largest humanitarian donors. Among these four donors, only the budget of EU institutions is stable for the coming years. Yet the specific implications of many of the announced donor ODA cuts for humanitarian budgets remain unclear.

Building on Chapter 1’s estimates for 2025 cuts (see Figure 1.2), this chapter takes the approach of examining which parts of the humanitarian system have the greatest exposure to donors that have announced cuts to ODA in 2025. These donors are referred to as ‘focus donors’ throughout this chapter.

Many humanitarian recipients are heavily dependent on donors that have announced cuts in 2025. In 2024, five contexts received 75% or more of their funding from these focus donors, with Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) being the most exposed. Many of these contexts have already experienced donor fatigue in recent years. UN agencies are also dependent on high levels of funding from donors that have announced cuts, specifically the World Food Programme (WFP), International Organization for Migration (IOM), Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), which all receive more than 60% of their humanitarian funding from these focus donors.

Specific humanitarian sectors are also more exposed to funding cuts than others. In 2024, the US was the largest donor across all humanitarian sectors analysed, and four sectors – nutrition, multi-purpose cash and basic needs, food security and agriculture, and logistics – all received more than 60% from the US, UK and Germany combined. Development funding to social sectors in protracted crisis countries, which is often critical to build resilience to crisis and mitigate future shocks, is also significantly exposed to ODA cuts. The most recent data shows that in 2023 up to 92% of development funding for key social sectors came from donors that have announced ODA cuts.

Although there is still uncertainty about exactly where the aid cuts will happen, this analysis of exposure suggests which areas of the humanitarian landscape are most vulnerable.

3.2: Which humanitarian donors are expected to make cuts?

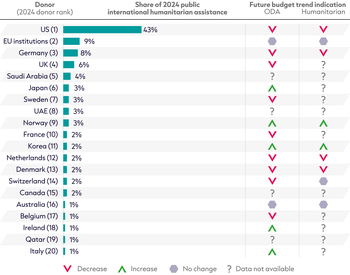

Figure 3.1: Almost half of the largest 20 humanitarian donors announced cuts to their future aid spending, including three of the top four

Changes in ODA and humanitarian assistance budgets for the 20 largest donors of international humanitarian assistance, 2025

Source: Authors based on Donor Tracker data, press reports and government budget documents.

Notes: Sweden’s ODA in 2025 remains stable compared to 2024 levels, however a decrease is indicated in the figure because the Swedish government has decided to cut ODA by 5% for 2026–2028. Directional arrows indicate any trend in budget as per sources, regardless of the magnitude of the increase or decrease. A question mark denotes that the trend is unknown. UAE = United Arab Emirates.

This figure was revised on 29 July 2025.

Almost half (9) of the 20 largest donors of humanitarian assistance have already announced reductions to their ODA budgets for 2025 or beyond. This comes on the back of 16 of the 20 largest donors reducing their international humanitarian assistance contributions in 2024 (see Figure 1.3).

The announced reductions by three of the four largest international humanitarian assistance donors from 2024 are of particular concern given the increasing reliance of the humanitarian system on them – in 2024, these four donors (US, EU institutions, Germany, and the UK) provided almost two-thirds (65%) of all international humanitarian assistance from public donors.

Of that group, only EU institutions have kept development and humanitarian budgets stable up until 2027, within its Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). Political negotiations for the 2028–2034 period began in March 2025, but it is too early to know what the implications of economic and political pressures on EU member states will mean for aid allocations under the new framework.

The ripple effects of the sweeping changes in the US to its foreign assistance and to its primary foreign assistance agency, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), are significant, and information about the scale of cuts and changes is still developing at the time of writing. Greater transparency on where the cuts will fall is urgently needed to track their impacts and for other actors in the system to adjust their focus accordingly.[1]

Announcements of intended cuts to aid have caused uncertainty and confusion – not least because it is challenging to translate high-level announcements into specific percentage decreases in the largest donors’ ODA or humanitarian assistance. In most cases, these budgetary decisions have yet to be agreed – or in the case of the US are not reliably available in the public domain. This has significant consequences for programming and financial planning, especially for those already facing liquidity challenges.[2]

At the time of writing, the following information is available on ODA or humanitarian budget cuts among major donors, aside from the US:

- Germany’s draft budget for 2025 proposes reductions to humanitarian assistance by 53%, and the budget for the Development Ministry was reduced by 8%. The newly formed government indicates in its coalition treaty the intention to reduce Germany’s ODA share as a percentage of gross national income (GNI), which might lead to further reductions.

- The UK government will cut its foreign assistance budget from the current target of 0.5% of GNI (already lowered from 0.7%) to 0.3% by 2027, partly to fund greater spending on defence. Current plans indicate cuts of around US $639 million in 2025/26 will be followed by much greater cuts of US $6.1 billion in 2026/27 and US $8.3 billion in 2027/28.[3]

- France cut its ODA budget for 2025 by about 19%, including a 37% reduction in the ‘ODA mission’ budget line, and postponed its target of allocating 0.7% of GNI to ODA by five years to 2030.

- Sweden has cut its ODA budget for 2026–2028 to US $5.1 billion from US $5.4 billion in 2023–2025, aligning with its earlier decision to abandon the target of allocating 1% of GNI to ODA.

- Switzerland announced cuts of US $282 million to its ODA budget for 2025.

Only four of last year’s top 20 humanitarian donors have indicated increases in their ODA or humanitarian budgets: Japan, Norway, Korea and Ireland. For Japan, Korea and Ireland, the anticipated percentage changes are within 5% and therefore much lower than the decreases by other donors (in relative and absolute terms). Norway announced an 8.6% increase in its 2025 ODA budget, including a 10% increase in its humanitarian assistance.

It is uncertain what role the Gulf donors – Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – might play in the international humanitarian system in 2025 and beyond given the lack of forward-looking data on their foreign assistance budgets. However, their geographical focus historically has been in the region, reacting to escalations in specific crises rather than driven by a publicly stated humanitarian aid policy. Their choice of partners is also different from other donors, with a much larger share of funding being channelled directly through recipient governments compared to UN agencies.

The remainder of this chapter examines the exposure of the humanitarian system only to donors that have announced cuts in either humanitarian budgets or total ODA budgets (where there is a possibility that humanitarian budgets will be cut as a result). All of the following statistics in this chapter examine these ‘focus donors’ only.

Therefore, the following sections do not examine donors that have not announced cuts as of April 2025. For example, other top 10 donors such as EU institutions, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Norway and the United Arab Emirates are not included in the graphs or statistics below.

3.3: How might anticipated cuts affect recipients?

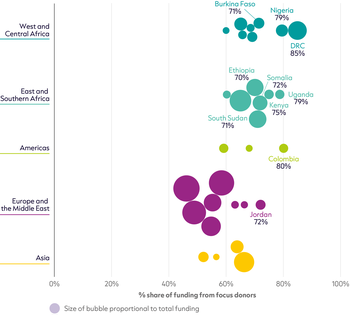

Figure 3.2: One-third of top 30 recipient countries of humanitarian assistance received 70% or more from donors that have announced cuts

Share of international humanitarian assistance from donors that have announced cuts to recipient countries by region, 2024

Source: Authors based on UN OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service (FTS). Also see sources for Figure 3.1.

Notes: The 10 countries displayed present in descending order the greatest reliance on donor funding from donors that announced cuts to their foreign assistance out of the 30 largest international humanitarian assistance recipient countries in 2024. Funding data includes international humanitarian assistance to each country for all donors, including governments, private funding and global pooled funds, as reported to FTS. DRC = Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The exposure of recipient countries to proposed donor budget cuts varies. The heavy reliance of some recipients on a few donors reflects challenges facing the wider system. Out of the 30 largest recipients of international humanitarian assistance in 2024, 10 received 70% or more of their humanitarian funding from donors that announced cuts to their ODA and/or humanitarian budgets for 2025 and beyond (Figure 3.3).

- DRC’s donor makeup in 2024 leaves it the most exposed to cuts, with 85% of its funding coming from donors that have announced aid cuts.

- Colombia, Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya all received 75% or more of 2024 funding from these donors.

The US is the largest donor to the 10 most exposed countries. The USAID memo published in late March 2025 containing a summary of terminated and retained projects paints a bleak picture for US foreign assistance in these countries, though accuracy of published information is unclear.

- Analysis of this memo in conjunction with other available data suggests on average the terminated share of USAID funding obligations across the 10 most exposed countries is expected to be 63%. This ranges between 35% (Somalia) and 92% (Colombia).

Reliance on other donors that have announced future budget cuts is far less concentrated, but nevertheless significant.

- Of the 10 most exposed recipients, the countries most reliant on German humanitarian funding were Jordan (14% of humanitarian funding) and Somalia (9%).

- The countries most reliant on UK humanitarian funding were Nigeria (14%), Ethiopia (14%) and Kenya (11%).

Some of the recipients most exposed to funding cuts were already experiencing growing donor fatigue, seen through the poor response to appeal funding requirements in 2024. These funding gaps are likely to grow in 2025, though that will ultimately depend on where donors choose to direct their possibly reduced funding envelopes and the revised requirements for these contexts.

- Ethiopia had the lowest share of response requirements met in 2024 (30%) out of the 10 contexts with the highest exposure to possible donor international humanitarian assistance budget cuts, followed by three contexts that were part of regional refugee responses: Uganda (34%), Colombia (41%), and Jordan (46%).[4]

- The remaining contexts received more than half of their response requirements, up to 71% in South Sudan.

Some of the largest recipients in 2024 are less reliant on the donors highlighted in Figure 3.2; they may be less exposed because of other donors, notably regional neighbours, directing greater attention to them.

- Palestine was the largest recipient of international humanitarian assistance in 2024 (see Figure 1.5) but received less than half of its funding (46%) from the eight donors with announcements of foreign assistance cuts. This is due to the United Arab Emirates (US $383 million), Qatar (US $102 million) and Saudi Arabia (US $92 million) providing large amounts of funding, alongside the EU institutions (US $187 million).

- Similarly, Yemen, the third largest recipient in 2024, may also be less exposed to donor cuts due to very high funding from Saudi Arabia in 2024 (US $817 million).

- Ukraine, the second largest international humanitarian assistance recipient in 2024, received large bilateral humanitarian support from Norway (US $263 million), the EU institutions (US $253 million) and Japan (US $123 million) in 2024. However this does not factor in broader development cooperation, such as direct budget support, for which the US was a major donor in previous years alongside EU institutions and other actors.

What is unclear from the data is the exposure of recipients to budget cuts from donors that channel a greater share of their funding through multilateral actors.

3.4: Which humanitarian sectors are most exposed to cuts?

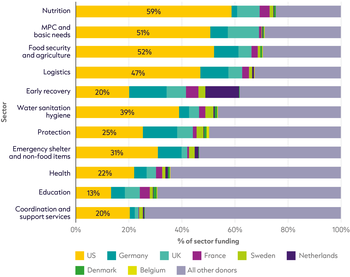

Figure 3.3: Food security, nutrition and multi-purpose cash sectors were among the most dependent on funding from donors that announced budget cuts

Share of donor funding by global humanitarian sectors, 2024

Source: Authors based on UN OCHA’s FTS data.

Notes: Funding both within and outside of response plans is included in the graph. Emergency telecommunications are included under logistics. Camp coordination/ management is included under coordination and support services. Funding to multiple clusters, multi-sector or other field clusters is excluded. Funding data is in constant 2023 prices. MPC = multi-purpose cash.

Reductions in budgets announced by large humanitarian donors will hit humanitarian sectors differently because exposure to this donor pool varies widely across sectors. Given the volume of funding from the US, sectors that are highly dependent on US funding are the most exposed (such as nutrition, multi-purpose cash and basic needs, food security and agriculture, and logistics):

- The US ranks as the top donor to 9 of the 11 sectors analysed, and the top focus donor to all. This includes nutrition where nearly 6 in every 10 dollars (59%) came from the US in 2024, whilst just over 5 in 10 dollars (52%) to Food security and agriculture came from the US. Multi-purpose cash and basic needs (51%) and logistics (47%) are also highly exposed to US cuts. WFP is a major actor in all of these sectors – with three quarters of funding received for food security and agriculture going to WFP.[5]

- Many sectors are also exposed to cuts from Germany, which is the second top donor to 3 of the 11 sectors analysed. In particular, early recovery (14% of the total), protection (13%) and logistics (11%) are particularly exposed.

- The UK also ranks as a top 3 donor in 4 of the 11 sectors analysed, including multi-purpose cash and basic needs (12%), nutrition (9%), education (6%) and water sanitation hygiene (4%).

The best-funded sectors in 2024 UN appeals are also the most exposed to funding cuts, which could have a levelling-down effect on funding gaps between sectors. However, the full effect is unknown as donors may choose to redirect funding and budget cuts could end up widening existing sectoral funding gaps.

- Logistics (58%), nutrition (54%) and food security and agriculture (49%) saw the largest proportion of their funding appeal requirements met in 2024. However, they are also among the most exposed to likely donor budget cuts, particularly due to their over-reliance on US funding.

- The remaining sectors, albeit mostly less exposed to likely donor budget cuts, were already under-funded in 2024. Share of requirements met included 20% for early recovery, 30% each for education and shelter/non-food items, and 43% for health. While at the time of writing the scale of revisions to response requirements is still under discussion, any additional donor budget cuts – as several have been announced already – are likely to deepen the degree of underfunding and unmet humanitarian needs in those response areas.

3.5: How exposed are different humanitarian organisations?

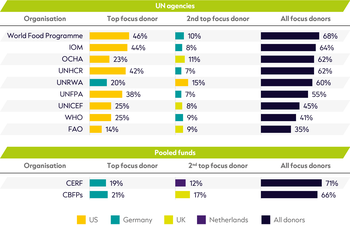

Figure 3.4: WFP and UNHCR are among the UN agencies most exposed to future donor budget cuts

Share of funding by humanitarian donor to UN agencies and pooled funds, 2024

Source: Authors based on UN OCHA FTS, UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP and IOM data, the CBPF data hub, CERF data, and on the Global Humanitarian Assistance dataset on private humanitarian funding.

Notes: Funding for UNICEF only reflects core funding (‘regular resources’) and humanitarian funding (‘other resources (emergency)’. All funding is included for WFP and UNHCR. Only funding captured on IOM’s crisis response dashboard is included. Funding to UNRWA, WHO, UNFPA, FAO and OCHA is based on FTS data. CBPF = country-based pooled fund; CERF = Central Emergency Response Fund; FAO = Food and Agriculture Organization; OCHA = Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; UNFPA = United Nations Population Fund; UNHCR = United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; UNICEF = United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund; UNRWA = United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East; WFP = World Food Programme; WHO = World Health Organization.

UN agencies vary widely in terms of how exposed they are to cuts. WFP received over two-thirds (68%) of its funding in 2024 from the donors that have announced cuts (46% from the US alone), whilst the humanitarian activities of WHO and FAO are the least exposed to humanitarian budget cuts according to FTS data, with only 41% and 35% from these donors:

- WFP and UNHCR (two of the largest UN agencies) are most exposed to donors that have announced cuts, receiving 68% and 62% from them, respectively.

- UNICEF, the other large agency delivering humanitarian assistance, is slightly more insulated with 45% of their funding coming from the focus donors.

- Exposure to the US is the biggest risk factor across nearly all UN agencies, as the US ranks top for all but one of the UN agencies analysed. Exposure to Germany and the UK is the next biggest concern for many agencies where they rank second in many cases, with between 7% and 10%.

As a result of their exposure to budget cuts, UN agencies have announced cuts in recent months. WFP announced a reduction of up to 30% of staff;[6] UNHCR announced a reduction of costs by 30% and reduction in the number of senior positions in half;[7] UNICEF said it is planning to operate with 20% less funding in 2026;[8] OCHA announced staff cuts by around 20%;[9] and IOM announced a reduction in donor funding of 30% and subsequent cuts of 20% of headquarters staff.[10]

In addition to workforce reductions, structural changes are underway. UNHCR has said it may close some country offices and rely on multi-country offices;[11] a merger of whole UN agencies as part of the UN80 Initiative is being considered, as well options to combine the operational aspects of the big UN agencies focused on aid.[12]

UN-managed pooled funds are also exposed to donor cuts, but not in the same way. The US is a smaller donor than other countries to the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) and country-based pooled funds (CBPFs), which have a broader base of funding:

- Germany (21% of CBPF total), the UK (17%) and the Netherlands (10%) are the largest donors to CBPFs that have announced budget cuts.

The CERF also has a wide base of funding, including from donors that have announced cuts, including Germany (19%), the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK (all 12%). Over 70% of CERF’s 2024 funding came from the eight focus donors. The pledges for CERF contributions in 2025 were 16% less than for the previous year.[13]

Despite recent cuts to the CBPFs and CERF, the ‘humanitarian reset’ and efforts under the Grand Bargain might position CBPFs well to attract a greater share of shrinking funding envelopes given their established position in channelling international humanitarian funding to local and national actors (see Figure 2.4). Most recently, it was announced that a proposal for one-third of global humanitarian assistance to be channelled through the CBPF, with additional funding for the CERF, is being explored as part of the humanitarian reset.[14] Reduced donor budgets may also lead to smaller donor grant management teams and reduced geographical presence, which could lead the same donors to instead channel more of their funding through CBPFs where they no longer have a country presence.

3.6: How exposed are countries in protracted crises from wider cuts to development ODA?

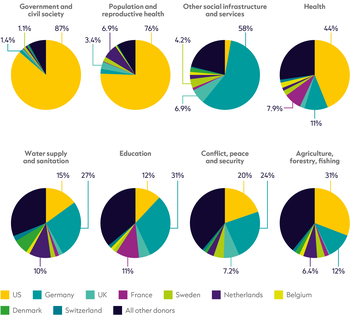

Figure 3.5: Up to 92% of ODA for key social sectors in protracted crises came from donors that announced international assistance cuts

Share of ODA to protracted crises by sector and DAC donor, 2023

Source: Authors based on OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System data.

Notes: Protracted crisis countries included in this graph are contexts with five or more years of country-specific humanitarian response plans in 2023. ODA data includes disbursements from DAC members.

Donor cuts will have far-reaching impacts on countries experiencing long-term crisis, beyond a reduction in humanitarian assistance – compounding the challenges these countries face (see Chapter 4).

Key social sectors in countries experiencing protracted crises are profoundly exposed by the announced cuts. In 2023, the latest year with complete data, up to 92% of development funding for key social sectors came from donors that have announced ODA cuts. The sectors most historically reliant on donors that have announced funding cuts are the government and civil society sector (92%) – which comprises different forms of support to the public sector and broader civil rights initiatives, including to women’s rights, human rights and ending violence against women and girls – and the population and reproductive health sector (91%). The US was the largest donor to these sectors in 2023.

- The US reports the bulk of its ODA to Ukraine under the government and civil society sector, which made up US $10.1 billion in 2023 and brought its share of funding to this sector across all protracted crises to 87%. Even discounting for the US funding to Ukraine, the nine donors highlighted in Figure 3.4 would make up half of the total funding to the government and civil society sector in protracted crises in 2023.

- The US was also the largest provider of health development funding to protracted crises in 2023 at US $862 million (44% of total), followed by Germany (11%) and France (7.9%). This funding includes support for the control of malaria, tuberculosis and infectious diseases, and for basic health care and nutrition – critical complements to humanitarian response.

The other social infrastructure and services; education; water supply and sanitation; and conflict, peace and security sectors in protracted crises all relied relatively less on US funding in 2023 but remain exposed to anticipated donor budget cuts.[15]

Around half of the bilateral development finance for agriculture in protracted crises in 2023 came from the US (31%), Germany (12%) and the Netherlands (6.4%) combined. The overall dependence for this sector on donors that announced cuts to their foreign assistance was 62% in 2023. Given the even higher exposure of humanitarian food-related sectors to funding cuts (see Figure 3.3), this risks further destabilising food systems in protracted crises.

Figure 3.1 and analysis on page 35 was revised on 29 July 2025 to reflect corrections provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark correcting an error in IHA as reported to OECD DAC

Footnotes

-

The picture emerging so far is based on the following published information:

-- Calculations based on a memo of retained and terminated USAID awards estimate the proposed US cuts to be in the range of 38% of total assistance and over 20% of humanitarian assistance. The final extent of the cuts in 2025 will not be known until after the end of the fiscal year. Source: Center for Global Development (CGD), 2025. USAID Cuts: New Estimates at the Country Level. CGD Blog, 26 March 2025. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/usaid-cuts-new-estimates-country-level.

-- Subsequent announcements of US funding cuts to Yemen, Afghanistan and other large-scale humanitarian crises will likely contribute to an even larger reduction in humanitarian funding. Source: OneAID Community, 2025. FLASH Update on USAID Humanitarian Award Terminations. OneAID Community Blog, 7 April 2025. Available at: https://www.oneaidcommunity.org/post/usaid-humanitarian-assistance-award-terminations.

-- The White House budget request for 2026 proposes cutting international humanitarian assistance to US $4 billion, a staggering 73% drop from 2024 funding levels. This remains a proposal and the final amounts will not be known until the request has been considered and approved by Congress. Source: CGD, 2025. Redefining America’s Interests? Trump’s FY2026 Budget Proposes Sweeping Cuts to US Foreign Aid. CGD Blog, 7 May 2025. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/redefining-americas-interests-trumps-fy2026-budget-proposes-sweeping-cuts-us-foreign-aid.

-

There are several factors preventing reliable estimates including: the ODA budget might be split across multiple government agencies and not all those budget components may be clearly delineated; for humanitarian assistance in particular, supplementary budget requests might be made throughout the year in reaction to new or escalating humanitarian crises; where cuts are announced to take place over multiple years, it is unclear how they will be spread between years.

-

Rabinowitz G., 2025. The Chancellor’s Spring Statement adds to the expected pain of the UK aid cuts. Bond News & Views, 27 March 2025. Available at: https://www.bond.org.uk/news/2025/03/the-chancellors-spring-statement-adds-to-the-expected-pain-of-the-uk-aid-cuts/

-

This percentage is calculated by adding up requirements and funding for the Uganda country components in 2024 across South Sudan, Sudan and Democratic Republic of the Congo Regional Refugee Response Plans, whilst the Colombia percentage is calculated by adding up requirements and funding for the Colombia Humanitarian Response Plan and the Venezuela Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan. Jordan is one of the countries within the Syria Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP) Plan.

-

The USAID memo on terminated and retained awards published in late March 2025 indicated that over 99% of USAID’s humanitarian funding obligations to WFP were retained, making the organisation an outlier in terms of the high share of retained awards. However, the extent of the cuts remains unclear and further decisions on cuts and retentions continue to be made: since March further reports indicated that US humanitarian funding to Afghanistan and Yemen were cut, both with high levels of food insecurity. While the impact of this on WFP’s core costs and programmes remains unclear, in the context of this high exposure to the declining donor base WFP announced to reduce its workforce by up to 30% by 2026.

-

Mersie A., 2025. WFP to cut up to 30% of staff amid aid shortfall. Devex, 25 April 2025. Available at: https://www.devex.com/news/exclusive-wfp-to-cut-up-to-30-of-staff-amid-aid-shortfall-109932

-

Farge E., 2025. UN food, refugee agencies plan deep cuts as funding slashed, memos show. Reuters, 25 April 2025. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/un-agencies-food-refugees-plan-deep-cuts-funding-plummets-documents-show-2025-04-25/

-

Nichols M., 2025. UNICEF projects 20% drop in 2026 funding after US cuts. Reuters, 16 April 2025. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/unicef-projects-20-drop-2026-funding-after-us-cuts-2025-04-15/b

-

Lederer E.M., 2025. UN humanitarian agency to cut staff by 20% due to ‘brutal cuts’ in funding. AP News, 12 April 2025. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/un-humanitarian-agency-staff-aid-cuts-trump-0896ba30d57a990fe441d5e74eefb81b

-

IOM, 2025. Update on IOM Operations Amid Budget Cuts. Available at: https://www.iom.int/news/update-iom-operations-amid-budget-cuts

-

Farge E., 2025. UN food, refugee agencies plan deep cuts as funding slashed, memos show. Reuters, 25 April 2025. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/un-agencies-food-refugees-plan-deep-cuts-funding-plummets-documents-show-2025-04-25/

-

Farge E. and Shiffman J., 2025. UN eyes big overhaul amid funding crisis, internal memo shows. Reuters, 2 May 2025. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/un-eyes-major-overhaul-amid-funding-crisis-internal-memo-shows-2025-05-01/

-

CERF, 2024. Huge scale of humanitarian crises worldwide requires surge in support for UN emergency fund, top officials say. CERF Press Release, 10 December 2024. Available at: https://cerf.un.org/sites/default/files/resources/CERF_HLPE_Press_Release.pdf

-

Byrnes T., 2025. Humanitarian Reset in Action: USG Tom Fletcher Details Agency Consolidation and System-Wide Reform at ECOSOC. LinkedIn, Tom’s Aid&Dev Dispatches, 16 May 2025. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/humanitarian-reset-action-usg-tom-fletcher-details-agency-byrnes-ddnee/

-

Funding for other social infrastructure and services – which includes employment, social protection and other basic social services – came primarily from Germany in 2023 (58%). Almost 80% of funding for other social infrastructure and services in protracted crisis countries came from donors that announced budget cuts, despite hardly relying on US funding (2.9%). This funding was mostly for multi-sector aid for basic social services in multiple crisis contexts (Ukraine, Afghanistan and Ethiopia were the largest recipients). The UK provided 6.9% of the total under this sector to protracted crises, mostly for social protection (e.g. in Ethiopia and Yemen).

Germany was the largest provider of development finance for protracted crises to education (31%), water supply and sanitation (27%) and to conflict, peace and security (24%) in 2023.

France provided 11% of ODA from DAC members to education in protracted crises in 2023 while the Netherlands (10%) and Belgium (7.0%) were both significant providers of development finance to water supply and sanitation.15 • Funding for other social infrastructure and services – which includes employment, social protection and other basic social services – came primarily from Germany in 2023 (58%). Almost 80% of funding for other social infrastructure and services in protracted crisis countries came from donors that announced budget cuts, despite hardly relying on US funding (2.9%). This funding was mostly for multi-sector aid for basic social services in multiple crisis contexts (Ukraine, Afghanistan and Ethiopia were the largest recipients). The UK provided 6.9% of the total under this sector to protracted crises, mostly for social protection (e.g. in Ethiopia and Yemen).