The shifting tectonic plates of broader crisis financing

Humanitarian assistance to countries affected by crisis sits within a wider funding landscape of ODA, including aid for development, peace and climate. Between 2014 and 2023, multilateral development banks (MDBs) increasingly engaged in fragile settings, tripling their funding to the top 20 humanitarian crises from US $3.5 billion to US $10.3 billion. However, in recent years these annual increases have stalled, returning to 2019 levels (i.e. before the COVID-19 pandemic) in 2023.

The steady increase in humanitarian funding contrasted with stagnating development and peace programming in crisis contexts between 2014 and 2023.[1] In 2023, the share of ODA for humanitarian assistance increased again for all protracted humanitarian response plan (HRP) contexts, excluding Ukraine. This trend is in direct contrast to the aims and commitments of the OECD DAC Nexus recommendation, which promotes ‘prevention always, development wherever possible, humanitarian action when necessary’.[2] As a result, humanitarian actors have been stretched across the spectrum of responses needed in crisis contexts, with inadequate funding for tackling root causes. Reduced funding for prevention also resulted in a rise of violence, insecurity and socioeconomic turmoil in fragile settings.[3]

While protracted crisis countries have become ever more reliant on humanitarian funding as the primary form of ODA, these countries are now seeing a stagnation and will likely see significant cuts to this funding. Preliminary data for 2024 suggests higher proportional cuts across humanitarian portfolios – even before the seismic impact of the 2025 donor cuts.[4]As the US now turns away from multilateralism, both the reduction in resources and the fundamental shifts in policy agendas are felt across institutions and sectors, with climate, gender and development programming deprioritised. This was evident in the recent 2025 Spring Meetings, as the World Bank communicated a return to focusing on jobs and infrastructure.[5]

Against the backdrop of an escalating global trade war, countries in humanitarian crisis face the dual challenge of reduced ODA combined with escalating debt levels. As humanitarian budgets are cut and the sector looks to return to providing assistance for basic needs, adequate reassurance that donors are stepping in to provide longer term development assistance to fill in the gaps and tackle protracted conflicts and their root causes remains to be seen. Addressing the financial needs of protracted crises will be a key issue for the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, which acknowledges the humanitarian–development– peace nexus in its draft outcome document.[6]

4.1: What is the mix of humanitarian, development and peace funding reaching protracted crises?

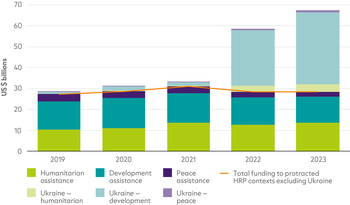

Figure 4.1: Increased funding to Ukraine hid a stagnation of wider crisis financing to protracted crises

Volumes of ODA from DAC members for development, humanitarian and peace to protracted HRP contexts

Source: Based on Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Creditor Reporting System (CRS).

Notes: Recipients vary between years. Data is in constant 2023 prices.

Over a decade ago, MDBs pivoted their strategies to provide more support to fragile, conflict and violence contexts as a way of enhancing stability and promoting sustainable development. As a result, volumes of wider crisis financing increased significantly to protracted crises. However, total ODA funding to humanitarian contexts has stagnated over the past five years, overshadowed by a large increase in assistance to Ukraine following the 2022 invasion.

- Protracted HRP contexts received 24% of all DAC donor ODA funding from 2019 to 2023. The volume of ODA from DAC members to protracted HRP contexts increased substantially between 2019 and 2023, from US $28.8 billion to US $67.5 billion. However, 97% of this increase is attributed solely to increased funding to Ukraine.

- Excluding funding to Ukraine, all other protracted HRP contexts received a steady US $28 billion of ODA per year over the same five year period – with the exception of 2021 (US $31 billion).

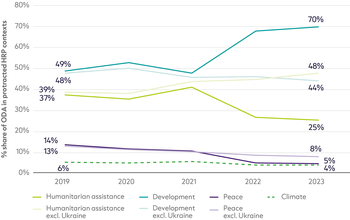

Figure 4.2 Humanitarian funding now outgrows development funding in protracted HRP contexts when Ukraine is excluded

Share of ODA to development, humanitarian, peace and climate from DAC donors to protracted HRP contexts

Source: Based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Recipients vary between years. Data is in constant 2023 prices.

Previous Global Humanitarian Assistance reports detailed the increased share of humanitarian funding going to protracted crises, and consequently the increased reliance on humanitarians to work on prevention, crisis response and resilience.[7] As a protracted crisis, Ukraine is an extreme outlier; it receives a significantly higher proportion of development funding than other protracted HRP crises. It is therefore important to understand trends in protracted HRP contexts both with and without Ukraine included. The share of humanitarian assistance in protracted HRP countries reduced from 41% in 2021 to 25% in 2023, but this is due almost entirely to the large volumes of development funding allocated to the Ukraine crisis. When excluding Ukraine, the share of humanitarian ODA continued to increase in 2023 as per previous trends, surpassing development ODA in 2022 and in 2023 recording its highest percentage share of ODA in protracted HRP contexts thus far.

- Development funding to protracted HRP contexts increased by 235% from 2019 to 2023 – the vast majority of this was allocated to Ukraine.

- Recipients with the highest share of development funding included Ukraine (88%), Mozambique (80%) and Cameroon (80%), and those with the lowest shares were Libya (30%), the Central African Republic (32%) and South Sudan (32%).

- The share of humanitarian ODA in protracted HRP contexts excluding Ukraine increased from 39% in 2019 to 48% in 2023 and now outmatches development ODA in these contexts. Venezuela, Yemen and Syria received the highest share of humanitarian funding, all at around 75%.

This large influx of development and humanitarian funding for Ukraine resulted in the relative reduction in the share of peace and climate funding across HRP contexts. Funding for peace programming remained comparatively low. Similarly, despite the heightened climate vulnerability of humanitarian contexts,[8] and the increase in volume from US $1.6 billion in 2019 to US $2.8 billion in 2023, climate finance made up a small share of ODA to HRP countries.

- Peace funding was a mere 5% of ODA in 2023 (US $3.2 billion), down from 12% in 2020 (US $3.7 billion).

- Libya, Iraq and Mali received the highest share of peace funding, at 43%, 23% and 19%, respectively. Cameroon, Ukraine and Yemen received the lowest proportions, at around 3–4%.

- Over this period, the relative share of climate finance across ODA averaged 5%, in comparison to 14% for non-HRP contexts.

- Excluding funding for Ukraine from the analysis reveals a smaller reduction in peace funding (13% to 8%), and an increase in climate funding from 6% in 2019 to 9% in 2023.

- The highest recipients in terms of share of ODA of climate finance were Burkina Faso (16%), Burundi (15%) and Mozambique (14%), which each received around the average for non-HRP contexts. The lowest recipients were Syria (1%), Ukraine (1%) and Venezuela (1%).

Most recent preliminary data for 2024 suggests the picture of nexus financing may be changing, as donors significantly reduced humanitarian aid in relation to overall ODA.

4.2: How do individual donors fund assistance across the triple nexus?

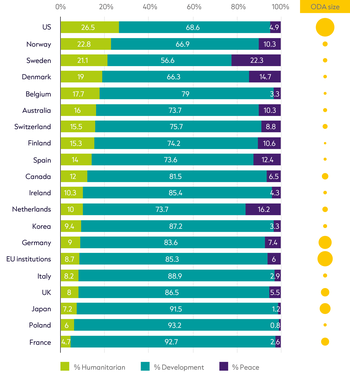

Figure 4.3: The largest humanitarian donors spend most of their funding on development aid

ODA from the top 20 DAC members for humanitarian, development and peace in 2023

Source: ALNAP based on OECD DAC CRS.

Notes: Humanitarian–development–peace classification follows the methodology of Development Initiatives’ research paper, Leaving no crisis behind with assistance for the triple nexus.[9]

Beyond the global trends, there is a large variation in terms of how much assistance each donor allocates across the humanitarian–development–peace and climate nexus. The United States is an outlier in providing a significantly higher proportion of humanitarian funding than other donors, while other large donors prioritise development spending.

- Across the top 20 donors, the average nexus split was 13% to humanitarian, 79% to development and 8% to peace in 2023.

- The United States gave the highest share of ODA to humanitarian assistance (26.5%); in contrast, France gave the lowest at 4.7%.

- Some of the largest humanitarian donors only contribute a small percentage of their ODA to humanitarian assistance, including Germany (9%), the EU (9%) and the UK (8%).

Peace funding is the lowest priority across the nexus for nearly all donors, with the exception of Sweden and the Netherlands. A handful of northern donors prioritise peace spending to the same extent as humanitarian, suggesting the implementation of intentional nexus financing strategies.

- Norway, Sweden and Denmark all contribute over 19% of their portfolio to humanitarian and over 10% to peace.

As the United States cuts wider development and peace funding – coupled with the generalised reduction of ODA budgets in favour of increased defence budgets – a narrowed focus on life-saving humanitarian action will likely be increasingly prioritised in 2025, leaving a growing gap in development finance. However, the largest DAC donors have little margin for manoeuvre for filling this gap, as Germany, the EU, the UK, Japan and France already give more than 83% of their portfolio to development. In this context, in-country nexus financing coordination becomes ever more relevant, through evidence-based financing strategies, joint planning and outcomes, promoting flexible and predictable funding, and supporting local leadership.

4.3: What is the trend in financing from multilateral development banks to humanitarian contexts?

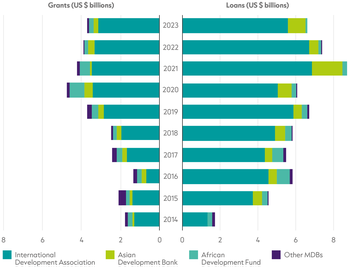

Figure 4.4: Volumes of funding from MDBs to humanitarian recipients have returned to pre-pandemic levels

ODA funding from MDBs to the top 20 humanitarian recipients

Source: Based on OECD DAC CRS, UN OCHA FTS.

Notes: Totals are ODA in the form of grants and loans from MDBs that report their funding to the OECD DAC CRS. The top 20 recipients of humanitarian assistance vary each year. Data is in constant 2023 prices.

Between 2014 and 2023, MDBs increasingly engaged in crisis settings and fragile contexts through a range of tools and financing mechanisms for providing grants and low-interest loans. This is evidenced by the increase in volume of funding to countries experiencing humanitarian crises, from US $3.5 billion to the largest humanitarian recipients in 2014 to US $10.3 billion in 2023 – a total of US $89.5 billion over 10 years. However, in parallel to the stagnating provision of development assistance to crisis contexts from DAC donors, these annual increases in volumes from MDBs have overall stalled.

- Across contexts and MDBs, there was a surge in funding from MDBs in 2021 during the pandemic, with US $12.9 billion disbursed to countries in crisis in 2021.

- By 2023, MDB grants and loans to crisis contexts were back to 2019 levels.

Funding from MDBs to crisis contexts remains largely developmental, focusing on long-term economic recovery. Only 4% of ODA provided by MDBs has a humanitarian purpose code. However, the top humanitarian recipient countries receive around 30–40% of funding of all MDB disbursements, a trend that has remained steady since 2016 (again except for 2021, when this rose to 45%). Yet while 10 years ago there was a relatively even split between the provision of grants and concessional loans, since 2021 64–67% of funding to the top humanitarian recipients has been disbursed in the form of loans.

- Over the past 10 years, grants to humanitarian crises have doubled in volume, whereas loans have tripled.

- Nevertheless, top humanitarian recipients have received a higher share of grants than other countries; over the same period, 78% of funding to countries not part of the top 20 humanitarian recipients was through loans.

The World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) remains the main channel of MDB financing to humanitarian crises, providing 81% of all MDB ODA funding to the top 20 humanitarian recipients between 2014 and 2023. IDA also provided the highest proportion of its funding to humanitarian recipients (38%) in comparison to other banks, whilst also providing the lowest proportion of grants after the Asian Development Bank. However in the past few years there has been a proportional decrease of IDA disbursements to crisis settings, and the United States contribution to the upcoming IDA replenishment is likely to be US $2.8 billion lower than pledged under the previous administration.[10]

- Since 2021 (IDA19, the replenishment from 2020 to 2023), IDA has decreased its share of disbursements to the top 20 humanitarian recipients. In 2021, 49% (US $10 billion) of its funding targeted these contexts. In 2023, the share reduced to 35% (US $8.7 billion).

- Estimations show that IDA may see a 15–20% reduction if current pledges are not honoured,[11] which in turn could lead to a US $1.5–2 billion loss in funding to the top 20 humanitarian recipients.

MDB funding to countries experiencing humanitarian crises is not allocated and disbursed equally across different contexts, with most funding channelled to a handful of crises, which are usually in countries with more established private sectors and state structures.

- From 2014 to 2023, Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Nigeria received 53% of all received disbursements.

- In contrast, despite being in the top 20 humanitarian recipients for all of the last 10 years, Syria received less than 0.1%. Similarly, a top 20 recipient for 9 years, Iraq received 0.1%, whereas Pakistan (a top 20 recipient for 2 years) received 5.5%.

4.4: What is the debt burden for protracted humanitarian crises?

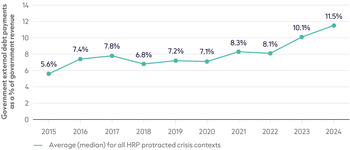

Figure 4.5: The average protracted crisis context is paying double on government debt payments in 2024 than a decade ago

Average (median) government external debt payments as % of revenue (protracted crisis contexts)

Source: ALNAP based on Debt Justice.

Notes: The figure includes data for protracted crisis contexts with an HRP in 2024; countries without data for the whole series were not included in the analysis.

Countries experiencing humanitarian crises are especially vulnerable to global economic instability, including the escalating uncertainty around trade, fluctuating commodity prices, inflation driving up exchange rates and capital flight.[12] Sovereign debt is on the rise, as is the cost of loan repayments.[13]

Across humanitarian contexts, governments are spending increasing proportions of their revenue on servicing commercial and concessional debt.[14] Current data on debt is available for 17 countries in protracted crisis; of these, governments were paying twice as much on average than they did a decade ago in external debt payments.

- A decade ago, only 3 of the 17 contexts in this subset were paying more than 10% of their government revenue to external debt payments; in 2024 the majority (11 of 17) of these contexts were paying more than 10%.

- Protracted crisis contexts that spent the highest proportion on external debt payments in 2024 were Sudan (42%), Cameroon (21%), Nigeria (20%), South Sudan (17%) and Niger (16%).

With overall aid budgets reducing and greater proportions of national revenue spent on debt servicing, there is less spending available for public services such as health, education and social protection, and climate action, risking further prolonging humanitarian crises. Furthermore, as climate disasters increase, countries are taking on ever larger loans to finance response and recovery[15] often prioritising economic policies favouring extractive industries to service these loans, further accelerating the climate crisis.[16]

Over recent years, the debt panorama has shifted in countries classified by the OECD as facing high fragility.[17] This classification is based on a country’s vulnerability to a range of factors; in 2024, out of 25 countries with an HRP, 11 were listed as facing extreme fragility and 10 as high fragility.[18] China was the largest bilateral creditor to contexts experiencing high fragility in 2022, and the second-largest creditor overall after IDA. Debt to private creditors has also increased over the past 10 years, although this remains limited in extreme fragility contexts[19] due to their lack of access to private markets.[20] As a result, there is a risk of countries moving away from multilateral structures to source borrowing, whilst in parallel there are increasing calls for a more inclusive multilateral treaty body on debt.[21]

During the pandemic there was a concerted effort to provide international support for debt sustainability, especially through the US $650 billion general allocation of Special Drawing Rights and the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, yet the OECD notes that these measures provided buffers that have now eroded, and the debt-to-GDP ratio of contexts with high and extreme fragility has increased.[17] Multilateral efforts to restructure sovereign debt, through the G20’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments, have been slow to take off.[22]At the 2025 World Bank IMF Spring Meetings, the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable released a new playbook for low-income countries,[23] aimed at improving transparency and coordination in debt restructuring processes. In addition, this Jubilee Year, policymakers and campaigners continue to present debt relief through a justice lens, in terms of both the unequal financial systems that have locked lower income countries in debt and the climate and historic debts of higher income former colonial powers.[24]

The potential transformational power of debt relief for countries facing humanitarian crises varies widely according to contexts and types of crises. While unlocking finance for governments party to internal armed conflicts or perpetrating human rights violations would not support the reduction of humanitarian need, countries hosting large numbers of refugees or facing the impacts of natural hazards and climate change could benefit significantly from debt relief.

- Three countries (Cameroon, Nigeria and Mozambique) paid more debt servicing costs (principal and interest repayments) than the total amount needed to fund their HRPs. Cameroon spent over three times as much on interest repayments than the HRP value (247% more), Nigeria spent more than twice as much (173% more), and Mozambique spent 9% more.

- In 2023, debt servicing costs were the equivalent of 86% of the Myanmar HRP, 48% of the Ukraine HRP, 41% for Mali, 40% for Chad, 35% for Ethiopia and 26% for Burkina Faso.

- Of the 19 contexts examined, 10 would have benefited more than 25% of their HRP funding requirement value if interest repayments were foregone.

- Debt relief for all protracted crises in 2023 could have unlocked US $8.1 billion in additional finance for these contexts (although 57% would have been destined solely to Ukraine, Nigeria and Ethiopia).

- However, for nine contexts debt servicing costs were below the equivalent of 25% of the HRP; this includes six contexts with over US $2 billion in HRP funding requests (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Yemen, Somalia, Afghanistan and Syria).

Footnotes

-

Development Initiatives, 2023. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023. Available at: https://devinit.org/resources/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2023/; OECD, 2025. States of Fragility 2025. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/states-of-fragility-2025_81982370-en.html

-

OECD, 2019. DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus. OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/5019. Available at: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/public/doc/643/643.en.pdf

-

OECD, 2025. States of Fragility 2025. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/states-of-fragility-2025_81982370-en.html

-

Obrecht A. and Pearson M., 2025. What new funding data tells us about donor decisions in 2025. The New Humanitarian, 17 April 2025. Available at: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2025/04/17/what-new-funding-data-tells-us-about-donor-decisions-2025

-

Saldinger A., 2025. Special edition: What to know as the 2025 World Bank-IMF Spring Meetings kick off. Devex, 21 April 2025. Available at: https://www.devex.com/news/special-edition-what-to-know-as-the-2025-world-bank-imf-spring-meetings-kick-off-109897; Banga A., 2025. Development is how we compete, grow, and stay secure. World Bank Blogs. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ voices/development-is-how-we-compete-grow-and-stay-secure

-

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), 2025. First Draft of the FfD4 Outcome Document. Financing for Sustainable Development Office. Available at: https://financing.desa.un.org/ffd4outcomedocument/firstdraft

-

Development Initiatives, 2023. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023. Available at: https://devinit.org/resources/global-humanitarian-assistance-report-2023/; OECD, 2025. States of Fragility 2025. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/states-of-fragility-2025_81982370-en.html

-

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 2023. The spiraling climate crisis is intensifying needs and vulnerabilities. Global Humanitarian Overview 2024. Available at: https://humanitarianaction.info/document/global-humanitarian-overview-2024/article/spiraling-climate-crisis-intensifying-needs-and-vulnerabilities

-

Development Initiatives, 2023. Leaving no crisis behind with assistance for the triple nexus. Available at: https://alnap.org/help-library/ resources/crisis-triple-nexus/

-

Mathiasen K., 2025. The Trump Administration and the International Financial Institutions: The Good, the Bad, and the Cynical. Center for Global Development blog, 7 May 2025. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/trump-administration-and-international-financial-institutions-good-bad-and-cynical

-

Saldinger A., 2025. Special edition: What to know as the 2025 World Bank-IMF Spring Meetings kick off. Devex, 21 April 2025. Available at: https://www.devex.com/news/special-edition-what-to-know-as-the-2025-world-bank-imf-spring-meetings-kick-off-109897

-

Jones T., 2025. US tariffs will intensify debt crisis in lower-income countries. Debt Justice blog, 4 April 2025. Available at: https://debtjustice. org.uk/blog/us-tariffs-will-intensify-debt-crisis-in-lower-income-countries

-

Saldinger A., 2025. Special edition: What to know as the 2025 World Bank-IMF Spring Meetings kick off. Devex, 21 April 2025. Available at: https://www.devex.com/news/special-edition-what-to-know-as-the-2025-world-bank-imf-spring-meetings-kick-off-109897

-

The New Humanitarian, 2023. Trends driving humanitarian crises in 2023 (and what to do about them). Available at: https://www. thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2023/01/03/ten-humanitarian-crises-trends-to-watch

-

Debt, Nature & Climate, 2025. Launch of Healthy Debt on a Healthy Planet: The Final Report of the Expert Review on Debt, Nature and Climate. Available at: https://debtnatureclimate.org/news/launch-of-the-final-report-of-the-expert-review-on-debt-nature-and-climate/

-

ActionAid, 2023. The Vicious Cycle: Connections Between the Debt Crisis and Climate Crisis. Available at: https://actionaid.org/ publications/2023/vicious-cycle

-

OECD, 2025. States of Fragility 2025. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/states-of-fragility-2025_81982370-en.html

-

Boral Rolland E., 2025. SoF 2025 Launch. GitHub. Available at: https://github.com/emileboralrolland/SoF-2025-Launch/tree/main Note that the Palestine Flash Appeal was included here as an HRP context.

-

Including Afghanistan, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

-

OECD, 2025. States of Fragility 2025. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/states-of-fragility-2025_81982370-en.html

-

Civil Society Financing for Development (FfD) Mechanism, 2024. Civil Society FfD Mechanism Submission to FfD4 Elements Paper. Available at: https://www.datocms-assets.com/120585/1729081275-civil-society-ffd-mechanism-submission-to-ffd4-elements-paper.pdf

-

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2023. The Human Cost of Inaction: Poverty, Social Protection and Debt Servicing, 2020– 2023. Available at: https://www.undp.org/publications/dfs-human-cost-inaction-poverty-social-protection-and-debt-servicing-2020-2023

-

Shalal A., 2025. Global roundtable sees rising debt risks for low-income countries as uncertainty mounts. Reuters, 23 April 2025. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/global-roundtable-sees-rising-debt-risks-low-income-countries-uncertainty-mounts-2025-04-23/

-

Baines W., 2025. 2025: The year we Cancel Debt, Choose Hope. Debt Justice news, 24 January 2025. Available at: https://debtjustice.org.uk/ news/2025-the-year-we-cancel-debt-choose-hope