Evidence into the effects of cash-based transfers provides lessons for the future and demonstrates why such programmes offer an effective response in challenging times.

Cash transfer programmes are at the frontline of national government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ranging from banknotes to e-money and debit cards to value vouchers, cash transfers are integral to many countries’ social protection systems, buffering the worst socio-economic effects of the crisis.

WFP supports 26 shelters and canteens in provinces across Ecuador. © WFP/Paola Solis

In 2019, the World Food Programme (WFP) transferred 2.1 billion USD – 38% of its total assistance – to 28 million people in 64 countries across the world.

But how did these cash transfers affect people’s lives? What can we learn from the evidence?

A recent learning exchange facilitated by ALNAP and the Cash and Learning Partnership (CaLP) discussed the challenges of evaluating cash assistance in humanitarian contexts. Issues including coordination, efficiency and cost-effectiveness, and the link between cash assistance and social protection are explored in detail in the organisations’ joint publication on the challenges in evaluating cash assistance in humanitarian contexts.

Now, a new evidence summary from WFP captures lessons from 23 WFP-commissioned evaluations and inter-agency humanitarian evaluations published between 2014 and 2020. It brings together evidence from Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Nigeria, Syria, El Salvador, Guatemala, Somalia, and others.

The summary highlights six main effects of cash transfer programmes implemented by WFP:

1. Food security gains

The majority of interventions where cash transfer programmes were applied – whether conditional or unconditional, and regardless of the modality (cash, voucher, a combination or ‘choice’) – indicated improved food security for beneficiaries for the duration of the programme. Where unrestricted cash was provided, high levels of expenditure on food were reported.

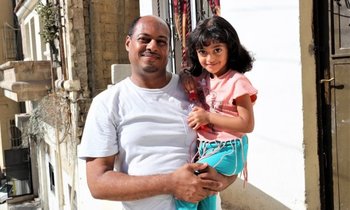

Jordan: Mohammad Bahomaishan and his family were enrolled in WFP’s food assistance programme. © WFP/Mohammad Batah

2. Enhanced livelihoods

An evaluation of the collective response to Typhoon Haiyan and an evaluation in Kenya, found that conditional cash transfer programmes, such as Cash for Assets (CFA), which included carpentry training, were more successful than unconditional cash transfers in supporting people to regain livelihoods.

In Kenya, host community traders – contracted to serve refugee beneficiaries – provided goods, labour and other services to refugee neighbours in return for cash.

South Sudan: the Food Assistance for Assets (FFA) programme focuses on asset creation activities that enhance food availability and access. © WFP/Gabriela Vivacqua

3. Improved dietary diversity

The use of cash and vouchers, as opposed to in-kind delivery, was shown to enhance dietary diversity in South Sudan and Zimbabwe, because cash could be used to buy a variety of foods not included with in-kind assistance.

In Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and Iraq, WFP beneficiaries in receipt of cash transfers had higher dietary diversity scores relative to non-beneficiaries.

Lebanon: An e-card allows families like Ahmad's to buy the food that they need, when they need it. © WFP/Edward Johnson

4. Investment in education and health where cash transfers were conditional

In Ecuador, the use of cash transfers conditioned on nutrition and health training was found to support beneficiaries’ investment in the education and health of their families.

5. Increased dignity

Whether conditional or unconditional, the use of cash – as opposed to vouchers – had positive effects on the dignity of beneficiaries in Somalia and Ecuador.

In Ecuador, for example, beneficiaries reported that they were less likely to be treated as 'second class' customers by vendors. In South Sudan, the predictability and timeliness of cash transfers also supported dignity.

South Sudan: Achok (25) visits the Sukkuthaar Market to buy food for her family after selling vegetables. © WFP/Gabriela Vivacqua

6. Supporting local economic development

Evaluation found positive effects of cash transfer programmes on local economic development. For example, a WFP-commissioned study in Lebanon found that for every US$1 spent directly on cash transfers, an additional US$1.51 was generated in local economic activity.

In Zimbabwe and Kenya, cash-based interventions supported local markets by stimulating demand for local goods; in Kenya, the monthly volume of sales by local traders increased by up to 94%.

Harare, Zimbabwe: Oppah Kanongara (aged 32) and her three children are receiving food assistance from WFP in the form of cash transfers. © WFP/Claire Nevill

However, it is important to note that some evaluations also found negative effects on the local economy where cash transfer schemes were extended over time. In Jordan, an evaluation of WFP’s cash-based response to the Syrian regional crisis recommended that WFP carefully monitor the local rental market and informal lending to ensure that cash did not have a negative effect on rent prices or create increased pressure for beneficiaries to pay off debts.

What lessons emerged from the evidence?

The summary provides twelve lessons to help enhance the positive effects of cash transfer programmes and reduce any risks which might impede effectiveness.

Lesson 1: Prioritise analysis, even under emergency conditions

Lesson 2: Plan across the humanitarian–development nexus from the design stage

Lesson 3: Adopt a coordinated approach

Lesson 4: Maximise the benefits of technology while keeping beneficiary experience in view

Lesson 5: Build flexibility into transfer values for maximum effectiveness

Lesson 6: Address national priorities and secure political will to ensure sustainability

Lesson 7: Prioritise sensitisation of local communities to reduce social tensions

Lesson 8: Temper beneficiary modality preference – often for unrestricted cash – with contextual conditions

Lesson 9: Communicate targeting criteria with a focus on equity

Lesson 10: Embed robust safeguards against beneficiary exploitation

Lesson 11: Build in gender and protection concerns from the start

Lesson 12: Adopt a systematic approach to accountability to affected populations