As a trans woman working in the humanitarian and development sectors, it’s increasingly galling to hear the exhortation ‘leave no one behind’ thrown around with gay abandon. The reality is that gay people are routinely abandoned, along with lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex and other people of diverse genders and sexualities.

Back in 2008, Chaman Pincha detailed the exclusion of the third-gender Aravani community from relief following the Indian Ocean Tsunami, one of the first detailed accounts of LGBTIQ+ exclusion. Aravani persons are neither women nor men: their gender is a non-binary. Official discrimination led to Aravanis not receiving ration cards (which offered only two gender options) and hampered access to shelter and other relief.

Almost 10 years later, not much had changed according to the DRR Good Practice Review in 2016:

Disaster managers do not, at present, consider the needs and capacities of LGBT people in their disaster planning or identify them as a specific audience for preparedness advice.

Ahead of the 32nd ALNAP Annual Meeting on relevance, I will draw on the work of the two organisations, Edge Effect and 42 Degrees, to argue that humanitarian action is often irrelevant for people with diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics. This can have devastating consequences. But principled and practical avenues for LGBTIQ+ inclusion are available for humanitarian actors.

Four exclusions and their consequences

There is a small but growing literature on exclusion of people with diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics in disasters, conflict and protracted emergencies. This literature includes Down By The River – a study on experiences of people with diverse genders and sexualities in TC Winston, and Pride in the Humanitarian System – which brought together community-based CSOs and humanitarian actors last year.

This literature collectively makes four key points about exclusion.

1. Marginalisation creates needs

Pre-emergency marginalisation of people with diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics undermines coping during crises and in recovery. Down By The River included stories of people thrown out of their homes, who were unwelcome in their villages, or in their faith community. Who were bullied at school. Who were sacked from jobs or had leases terminated when employers or landlords found out about their gender or sexuality. Who experience discrimination in hospitals and while seeking other public services. And all that in a country where sexual orientation and gender identity are constitutionally protected characteristics.

In 70 other countries consensual same-sex acts are criminalised.

All of this means that people with diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics often struggle to establish livelihoods and networks that sustain through crises and into recovery. Addressing this does not equate to unprincipled ‘special treatment’ for LGBTIQ+ people. The impartiality principle recognises that needs vary. Humanitarian actors should make themselves aware of the needs created by pre-emergency marginalisation.

2. We often avoid official responses

Everyday experiences of violence and discrimination lead people with diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics to take their own protective measures. Just because it’s a crisis it doesn’t mean that violence and discrimination stops. Host communities may be as discriminatory as our fellow citizens. And some people blame us for crises, our lives triggering divine intervention as collective punishment. So it’s not hard to understand why people with diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics often don’t try to access official relief. Instead we tend to rely our own trusted informal networks, safe houses, and community resources. Those resources may be heavily compromised in crises, but often they are the best we have.

3. The humanitarian system is diverse SOGIESC unaware

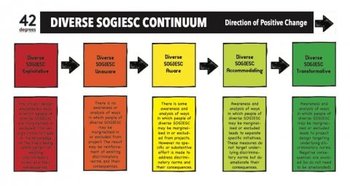

The humanitarian system – its frameworks, guidance and tools – often seems unaware of the needs of people with diverse genders, sexuality and sex characteristics. There are some exceptions -- for example IASC GBViE guidance -- but that’s the exception rather than the rule. We’ve found it useful to assess humanitarian and development programs using this diverse SOGIESC continuum tool, which encourages analysis and design that recognises, ameliorates, or challenges heteronormative, cisnnormative, binary and dyadic assumptions that underpin exclusion. Where would you place humanitarian programs of your organisation?

4. It’s a vicious cycle

Exclusion during emergencies (even inadvertent exclusion) reinforces pre-emergency marginalisation and breaches protection principles. Chaman Pincha’s account of Aravani marginalisation after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami is a devastating example of how diverse SOGIESC unaware or exploitative humanitarian action can reinforce pre-emergency marginalisation (and breach protection principles). Some in the Aravani community members relied on sex work to access relief, and their exclusion from official support was there for everyone to see.

Adding LGBTIQ+ to lists is not a solution

Some change is afoot, but it doesn’t go nearly far enough. Reports, policy and practice guidance are increasingly including definitions of sexual orientation and gender identity. And versions of that initialism ‘LGBTIQ+’ often appear in the lists of marginalised people that humanitarians are urged to consider or consult with. But there is usually precious little guidance on how to do that. What should humanitarians in shelter, education, WASH and other areas be considering? How can people with diverse gender, sexuality and sex characteristics be consulted (especially in contexts of criminalisation and high levels of stigma)? What should humanitarians ask? And what should they do with the information that’s shared?

Parts two and three

This is one of three posts I will author in ALNAP's Annual Meeting blog series on relevance. In the next two posts we’ll explore ways of hurdling common barriers that stop humanitarian staff and organisations from taking action (part two) and explore community-based response and genuine collaboration with community members – including recommendations from Pride in the Humanitarian System (part three).